【요가

[범어]yoga】

❋추가참조

◎[개별논의]

○ [pt op tr]

○ 2019_1106_112146_nik_fix 화순 영구산 운주사

○ 2019_1106_094939_can_exc 화순 영구산 운주사

○ 2019_1106_123823_can_fix 화순 영구산 운주사

○ 2019_1105_133624_can_exc 순천 조계산 선암사

○ 2019_1105_154843_can_fix 순천 조계산 송광사

○ 2019_1201_143552_nik_fix 원주 구룡사

○ 2019_1201_162859_nik_exc 원주 구룡사

○ 2020_0904_092429_can_ori_rs 여주 신륵사

○ 2020_0905_164927_can_ori_rs 오대산 적멸보궁

○ 2020_0907_112827_nik_ori_rs 양산 보광사

○ 2020_0908_154353_nik_ori_rs 합천 해인사

○ 2020_0910_113043_can_ori_rs 속리산 법주사

○ 2020_1002_120004_nik_exc_s12 파주 고령산 보광사

○ 2020_1017_152050_can_exc 삼각산 화계사

○ 2018_1023_165825_nik_exc 예산 덕숭산 수덕사

○ 2019_1104_094549_can_exc 구례 화엄사

○ 2019_1104_133655_can_exc 구례 화엄사 연기암

○ 2019_1104_171821_can_fix 구례 지리산 연곡사

○ 2019_1104_133956_nik_fix 구례 화엄사 연기암

● [pt op tr] fr

★2★

❋❋추가참조 ♥ ◎[개별논의]

○ [pt op tr]

● From 고려대장경연구소 불교사전

요가

요가[범어]yoga

[1]인도의 전통적인 수행의 수단을 일컫는 말.

정신을 통일하여 절대자와의 합일 혹은 해탈에 이르는 방법.

요가 철학에서는 마음의 작용을 제어하는 것이라고 정의된다.

⇒

[원][k]유가[c]瑜伽

[2]유가의 원어.

⇒

[원][k]유가[c]瑜伽

● From Korean Dic

요가

요가(yoga 범)[명사]인도 고유의 심신 단련법의 한 가지.

자세와 호흡을 가다듬어 정신을 통일·순화시키고,

초자연적인 힘을 얻으려는 수행법.

● From Kor-Eng Dictionary

요가 yoga.ㆍ ~의 수련자 a yogi.ㆍ ~를 하다 practice yoga.

● From 한국위키 https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/

● 요가 네이버백과 사전참조

● from 한국 위키백과https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/요가

한국 위키백과 사전참조 [불기 2566-12-29일자 내용 보관 편집 정리]

사이트 방문 일자 불기2566_1229_1011

>>>

요가

123개 언어

문서

토론

읽기

■편집

역사 보기

위키백과, 우리 모두의 백과사전.

요가 명상을 하고 있는 시바신

인도 델리의 비르라 만디르(Birla Mandir) 사원에 있는 요기 조각상

| 힌두교 |

|---|

|

| 펼치기

기본개념 |

| 펼치기 믿음과

수행 |

| 펼치기 경전과 그

성립 |

| 펼치기 철학 |

| 펼치기 종파 |

| 펼치기 관련

항목 |

산스크리트어 요가(Yóga)의 뜻은 다양하다. 제어(Control)[1] · 합일(Union)[2] · 수단(Means) · 방편(Means)[2] 등의 의미가 있다. |

이러한 영향에서 전개된 힌두교의 종교적 · 영적 수행 방법의 하나로도 알려져있다.

힌두교에서는 "요가란 실천 생활 철학에 철저함을 추구하는 것"이라고 정의하고 있다.

요가학파는 힌두교의 정통 육파철학 중 하나다.

요가 학파의 주요 경전으로 《요가 수트라》가 있다.

요가 수트라 제일 첫머리(정확히는 두 번째 구절)에서는 요가를

"마음의 작용(心作用 · Citta-Vṛtti)의 지멸(止滅 · Nirodhaḥ)"이라고 정의하고 있다.[3]

요가는 또한 인도에서 발생한 여러 종교의 믿음과 수행과도 관련이 있다.[4]

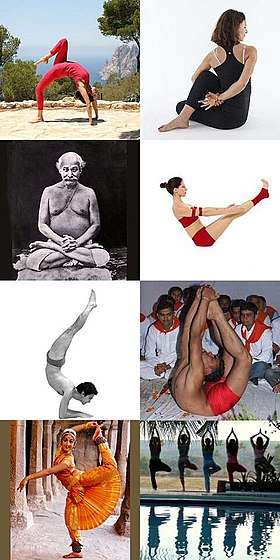

인도 밖에서 요가는 흔히 하타 요가의 아사나 수행(자세 취하기)이나 운동의 한 형태로 알고 있다.

최근 뉴욕에서는 요가가 크게 유행했다.[5][6]

힌두교 경전에는 우파니샤드,

《바가바드 기타》,

파탄잘리의 《요가 수트라》,

《하타 요가 프라디피카》,

《시바 삼히타》 등이 있다.

여기에서는 요가의 여러 측면을 기술하고 있다.

요가의 주요 분류로는 하타 요가 · 카르마 요가 · 즈나나 요가 · 박티 요가 · 라자 요가 등이 있다.

《바가바드 기타》에서 크리슈나는 아르주나에게 카르마 요가 · 즈나나 요가 · 박티 요가에 대해 설명하고 있다.[7]

박티 요가에 대한 최고의 힌두교 경전은 《바가바드 기타》와 《바가바타 푸라나》다.

이 둘을 비교하면 《바가바드 기타》에서는 박티가 보다 이론적으로 다루어져 있다.

반면,《바가바타 푸라나》에서는 박티가 보다 실천적으로 다루어져 있다.[8]

라자 요가는 파탄잘리의 《요가 수트라》에 의해 확립되었다.

요가 학파는 파탄잘리에 의해 성립되었다.

이 요가학파는 《요가 수트라》를 주요 경전으로 한다.

그리고 라자 요가를 수행법으로 한다.

역사[■편집]

인더스 문명의 인장[■편집]

인더스 문명(기원전 약 3300-1700년)의 유적지에서 발굴된 여러 인장들 중에서

일부 인장들은 사람이 요가나 명상(meditaion) 자세를 취하고 있는 듯한 모양을 하고 있었다.

이에 대해 고고학자 그레고리 포셀은 "요가의 시초가 되는 제의적인 운동의 형태"라고 보며,

이에 대한 증거가 모이고 있다.[9]

그는 후기 하라파의 유적지에서 발견된 16개의 요기(Yogi) 조각에 대해

"제의적인 수양과 집중"이라고 말한다.[10]

이 형상은 요가 자세로 "신들과 인간 모두가 행했던" 것이라고 본다.[9]

이중 가장 잘 알려진 형태는 파슈파티 봉인(Paśupati 封印)으로,[11]

발견자인 존 마샬은 이것이 시바의 원형이라고 주장한다.[12]

현대의 많은 고고학 권위자들은 이 파슈파티(Paśupati: 동물의 왕)[13] 가 시바나 루드라를 나타낸다고 본다.[14][15]

갤빈 플러드는 이것이 피상적인 결론이라고 말하면서,

파슈파티 봉인이 요가 자세로 앉아 있는 시바나 루드라 또는 요기의 형상인지

그냥 사람의 형상인지는 정확하게 알 수는 없다고 주장한다.[12][16]

요가 학파[■편집]

개요[■편집]

요가 학파(Yoga學派) 또는 요가파(Yoga派)는 요가 수행에 의해 모크샤(해탈)에 도달하는 것을 가르치는 학파로,

힌두교의 정통 육파철학 중 하나이다.

요가 학파의 근본 경전은 《요가 수트라》로,

힌두교 전통에 따르면 파탄잘리가 그 편찬자이다.

그러나 《요가 수트라》가 현재와 같은 형태로 편찬된 것은

기원후 400∼450년경인 것으로 여겨진다.[17]

요가 학파의 철학에는 불교의 영향이 있다는 것도 인정되지만,

요가 학파의 철학은 삼키아 학파의 철학과 거의 동일하다.[18]

철학면에서 삼키아 학파와의 상이점으로는,

요가 학파에서는 절대자로서의 최고신을 인정한다는 것만이 거의 유일한 차이라고 할 수 있다.

요가 학파에서는

일상생활의 상대적인 동요를 초월한 곳에

절대 고요(絶對靜)의 신비적인 경지인 사마디(삼매)의 상태가 있으며,

이 사마디의 경지에 도달할 때

요가, 즉 절대자와의 합일이 실현된다고 생각하였다.

요가 학파에서는 이와 같은 수행을 요가라고 부르고,

그 수행을 행하는 사람을 요기(Yogi) 또는 요가행자(Yoga行者)라고 이르며

그 완성자를 무니(牟尼 · 聖者)라고 일컫는다.

이와 같은 사마디라는 신비적 경지는

다른 여러 힌두 학파의 해탈의 경지와 일치하는 것이기

때문에 각 힌두 학파들이 모두 요가의 수행을 실천법으로써 사용하고 있다.[17]

라자 요가[■편집]

요가 학파에 따르면 "요가"라는 낱말의 의미는

"마음의 통일을 이루는 것"으로

요가는 "마음의 작용(心作用 · 심작용)의 지멸(止滅)"이라고 규정짓고 있다.[19][3]

따라서 외부적인 속박을 떠남과 동시에

내부적인 마음의 동요를 가라앉게 하지 않으면 안 된다.[19]

삼키아 학파와 요가 학파의 철학에 따르면,

마음의 작용(心作用 · 심작용)이란

푸루샤(神我 · Cosmic Spirit)가 프라크리티(自性 · Cosmic Substance)를 자기 자신으로 동일시하는 것을 의미한다.

삼키아 학파에 따르면 이러한 동일시가 있으면 우주와 현상이 전개되고("주관과 객관의 구별이 있는 상태") 이러한 동일시가 사라지면 우주와 현상이 해체되어 사라진다

("주관과 객관의 구별이 없는 상태").

이러한 우주적 전개와 해체의 과정을 설명하는 삼키아 학파의 철학을 개별적인 영혼에 적용한 것이 요가 학파의 철학이다.[18]

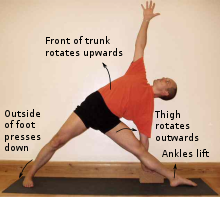

요가 학파에서는 요가 수행의 전제로 계율들, 즉 행하지 않아야 될 것들(① 야마)과 적극적으로 행하여야 할 것들(② 니야마)에 대해 말한다.

그리고 이 두 범주의 계율을 바탕으로 하는 상태에서 다음의 실천적인 수행을 행해야 한다고 말한다.

먼저 한적하고 고요한 장소를 선택하여 좌정하되,

좌법(③ 아사나)에 쫓아 다리를 여미고

호흡(④ 프라나야마)을 가라앉게 하여 마음의 산란을 막아서,

5관(五官)을 제어(⑤ 프라챠하라)하여 5감(五感)의 유혹을 피하고,

다시 나아가 마음을 집중(⑥ 다라나와 ⑦ 디야나)시킨다.

그리하여 마침내 ⑧ 사마디(삼매 · 三昧 · 等持)에 도달한다.[19]

요가 학파에 따르면 사마디에도 천심(淺深)의 구별이 있어서

사비칼파 사마디(Savikalpa samādhi · 유상삼매 · 有想三昧)와

니르비칼파 사마디(Nirvikalpa samādhi · 무상삼매 · 無想三昧)로 나뉜다.

전자는 대상의 의식을 수반하는 사마디이며,

또한 아직은 대상에 속박되어 대상에 의해 제어되고 있고

또 심작용(心作用)의 잠재력을 가지고 있으므로

사비자 사마디(Savija samādhi · 유종자삼매 · 有種子三昧)라고도 일컫는다.

그러나 니르비칼파 사마디에 들어가면

이미 대상의식(對象意識)을 수반하지 않고

대상에 속박되지 않으며,

그 경지에 있어서는 심작용(心作用)의 여력마저도 완전히 없어지기 때문에,

이것을 니르비자 사마디(Nirbija samādhi · 무종자삼매 · 無種子三昧)라고도 한다.

니르비칼파 사마디 또는 니르비자 사마디의 경지가 참된 요가이며

이 경지에서 푸루샤는 관조자로서 그 자체 속에 안주한다.[19]

후대에는 이와 같이

① 야마 · ② 니야마 · ③ 아사나 · ④ 프라나야마 · ⑤ 프라챠하라 · ⑥ 다라나 · ⑦ 디야나 · ⑧ 사마디의

여덟 단계로 구성된 라자 요가(Raja Yoga: 왕의 요가 또는 요가의 왕도) 대신에,

곡예와 같은 무리한 육체적 수행을 행하는 하타 요가의 실천도 성행하였다.[19]

다른 종교와의 관계[■편집]

요가와 불교[■편집]

요가는 다른 인도의 종교들의 종교적 믿음과 수행에 영향을 주었다.[4]

요가의 영향은 불교에서도 발견된다.[21][22]

석가모니가 한 명상법은 불교가 생기기 전의 명상법인데,

인도에 그런 명상법은 요가밖에 없었다.

석가모니는 요가의 숨을 멈추는 쿰바카를 반대하고,

짧게 들이쉬고 길게 내쉬는 호흡법인 안반념법을 주장했다.

불경에는 석가모니를 "최고의 요가 수행자여" 라고 부르기도 한다.

한국의 불교 신자들이 반야심경과 함께 기본적으로 암송하는

천수경의 신묘장구대다라니에도 요가와 관련된 다라니 구절이 나온다.

위대한 요가의 힘을 성취한 님을 위해서 쓰와하

신비로운 힘의 방편을 지닌 요가수행자의 님을 위해서 쓰와하

티베트의 라마교는

수행법으로 두 가지를 제시한다.

하나는 경전에 따른 수행으로 '람림(Lamrim)'이고

다른 하나는 힌두요가를 결합한 밀교 수행이다.[23]

중기 대승불교를 요가불교라고 부른다.

유가사지론이 유명하다.

같이 보기[■편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에

관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다. 요가 |

참선

심작용: 유식설 · 제8아뢰야식 · 말나식 · 오위백법

유식유가행파

요기

요기라지

애크로요가(en:Acroyoga) 애크로밸런스(en:Acrobalance)

플라잉 요가 앤타이그래비티(en:AntiGravity, Inc)

요가 운동

각주[■편집]

↑ Flood 1996, 94쪽

↑ 이동:가 나 Apte 1965, 788쪽

↑ 이동:가 나

요가 학파에서 요가란 "마음의 작용(心作用)의 지멸(止滅)"이라고 한 것은

요가 학파의 경전인 《요가 수트라》의 제일 첫머리에 나오는 말이다.

요가에 대한 이 정의는

《중용》의 중화(中和)에 대한 설명인

"喜怒哀樂之未發 謂之中 發而皆中節 謂之和(희노애락지미발 위지중 발이개중절 위지화: 희노애락이 나오지 않은 상태를 중(中)이라 하고

희노애락이 나오되 질서가 있는 것을 화(和)라 한다)"에서 나타나는 중(中)의 개념과 유사성이 있다.

서로 대비시켜 보면 마음의 작용(心作用)은

희노애락(喜怒哀樂)에, 지멸(止滅)의 상태는 미발(未發)의 상태에 대응한다.

힌두 철학에서 마음의 작용이 지멸된다는 것은 비즈냐나(식)가 지멸되는 것을 의미하며

즈냐나(지혜)가 지멸되는 것을 뜻하지 않는다.

오히려 비즈냐나(식)의 지멸이 즈냐나(지혜)가 나타나게 하는 직접적인 방법 또는 원인이라고 본다.

이것은 불교에서 선정에 의해 지혜(반야)가 드러나게 된다고 말하는 것과 동일한 개념이다.

불교의 무심(無心) 또는 무념(無念)은 지혜(반야)가 소멸되는 것이 아니라

마음의 작용인 아뢰야식이 완전히 소멸되는 것이다.[20]

사실상 마찬가지로, 《중용》에서 희노애락이 나오지 않은 상태인 중(中)은 희노애락을 느끼지 못하는 목석의 상태가 아니라

희노애락에 휘둘리지 않는 중용의 덕 또는 힘이 발휘되는 상태이다.

중용의 덕 또는 힘이 점점 더 발휘되면 될수록

희노애락이 질서 있게 나타나는 상태인 화(和)가 점점 더 완성되게 된다.

↑ 이동:가 나 The Yoga Tradition: its history, literature, philosophy and practice By Georg Feuerstein. ISBN 81-208-1923-3. pg 111

↑ <뉴욕스케치>도심 공원에서 요가 강습 Archived 2004년 10월 15일 - 웨이백 머신 뉴시스 2007-08-09

↑ 커버스토리 2002·가을·맨해튼 '패션피플'의 라이프 스타일 Archived2004년 10월 15일 - 웨이백 머신 동아일보 2002-09-26

↑ Flood 1996, 96쪽

↑ Kumar Das 2006, 172–173쪽

↑ 이동:가 나 Possehl 2003, 144쪽

↑ Possehl 2003, 145쪽

↑ Marshall, Sir John, 《Mohenjo Daro and the Indus Civilization》, London 1931

↑ 이동:가 나 Flood 1996, 28–29쪽

↑ 파슈파티(Paśupati)를 동물의 왕(Lord of Animals)으로 번역하는 것에 대해서는 다음을 참조하시오: Michaels 2004, 312쪽

↑ Keay 2000, 14쪽

↑ Flood 2003, 143쪽

↑ Flood 2003, 204–205쪽

↑ 이동:가 나 동양사상 > 동양의 사상 > 인도의 사상 > 정통바라문 계통의 철학체계 > 요가파, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

↑ 이동:가 나 Bernard 1947, 89쪽

↑ 이동:가 나 다 라 마 동양사상 > 동양의 사상 > 인도의 사상 > 정통바라문 계통의 철학체계 > 요가파 > 요가, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

↑ 《유가사지론》 13권

↑ "Yoga," Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia 2007 © 1997-2007 Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Archived 2005년 5월 21일 -

웨이백 머신 인용문

: "The strong influence of Yoga can also be seen in Buddhism,

which is notable for its austerities, spiritual exercises, and trance states."

↑ Zen Buddhism: A History (India and China) By Heinrich Dumoulin, James W. Heisig, Paul F. Knitter (page 22)

↑ 여적 삼보일배 경향신문 2003-05-21

참고 문헌[■편집]

Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). 《The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary》 (영어). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0567-4. (fourth revised & enlarged edition).

Bernard, Theos (1947). 《Hindu Philosophy》 (영어). New York: Philosophical Library.

Flood, Gavin (1996). 《An Introduction to Hinduism》 (영어). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0.

Flood, Gavin (Editor) (2003). 《The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism》 (영어). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-4051-3251-5.

Keay, John (2000). 《India: A History》 (영어). New York, USA: Grove Press. ISBN 0802137970.

Kumar Das, Sisir (2006). 《A history of Indian literature, 500–1399》 (영어). Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 9788126021710.

Michaels, Axel (2004). 《Hinduism: Past and Present》 (영어). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08953-1.

Possehl, Gregory (2003). 《The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective》 (영어). AltaMira Press. ISBN 978-0759101722.

외부 링크[■편집]

국내 요가의 현황[깨진 링크(과거 내용 찾기)]

● 나무위키

https://namu.wiki/w/요가

★★★

이름

한글

요가

영어

Yoga

중국어

瑜伽

힌디어

योग

펀자브어

ਯੋਗ

프랑스어

Le yoga

러시아어

йога

1. 인도로 돌아보는 요가의 개괄

1.1. 요가의 역사적 개요

1.2. 요가 철학의 형이상학

1.3. 요가 수행의 이론

1.3.1. 요가에서 말하는 삶의 단계

1.3.2. 싸마디

2. 요가의 종류

2.1. 아쉬탕가 요가(Ashtanga Yoga)

2.2. 아헹가 요가(Iyengar Yoga)

2.3. 빈야사 요가(Vinyasa Yoga)

2.4. 비크람 요가(Bikram Yoga)

2.5. 테라피 요가(Therapy Yoga)

2.6. DDP 요가(DDP Yoga)

2.7. 플라잉 요가(Anti gravity Yoga, Aerial Yoga)

3. 요가와 불교

4. 요가와 스트레칭

5. 국가별 요가의 입지

5.1. 인도

5.2. 서구권

5.3. 한국의 요가

5.3.1. 그 외 양생 단체

5.3.2. 커플 유튜버들의 컨텐츠

6. 요가의 자세

1. 인도로 돌아보는 요가의 개괄[편집]

인도의 정신수련법으로 알려진 요가.

요가철학 혹은 요가학파의 역사는 꽤 깊어서 기원전까지 거슬러 올라가기도 한다.

Yoga는 산스크리트어 'yuj'를 근원으로 '결합하다'는 뜻인데,

대체로 특정한 자세를 통해

몸과 마음을 수련하여

정신적으로 초월적자아와 하나 되어 무아지경,

혹은 삼매경,

황홀경의 상태에 도달하는것을 목표로 한다.

여담으로

대구광역시 달성군 비슬산에 있는 유가사(瑜伽寺)[1]와

동화사의 전신인 유가사가 바로 여기에서 나왔다.

요가가 기원전까지 거슬러 올라간다는 말에

무슨 말이냐고 의아해할 사람이 있을 것이다.

기원전이란 즉,

단순히 기원전 오백 년에서 천 년 정도 짧은 세월(?)을 말하는 것이 아니고

인도 아대륙에 아리아인들이 도착하기 이전

하라파 문명[2]에 요가의 기원이 존재한다는 학설이다.

간략히 말하자면,

일반적으로 현재 우리가 생각하는 힌두이즘으로 대변되는 인도 문화는

기원전 2000-1500년경 아리아인들이

인도 아대륙에 진입하여 형성해낸 문화이다.

그 전에는 하랍빠 문명이라는

인도 아대륙의 토착 문화가 있었으며,

이들의 문화는 풍요제의 성격을 띠는 신상숭배적인 것으로,

자연신을 숭배하였던 베다 문화와는 많이 달랐다.[3]

이러한 베다 문화는 뿌라닉 힌두교로서 나중에 신상 숭배에 다시 천착하게 된다.

요가는 이렇게 브라만교-힌두교로 이어지는 베다 문화에 그 뿌리를 두고 있다고 믿어 왔다.

그러나 하랍빠와 모헨조다로에서의 일부 고고학적 발견은

아리안 지배 이전 드라비다 문화에서부터 요가의 기원이 시작되었다는 가능성을 제시한다.

예컨대 모헨조다로에서는

시바 신의 원형으로 생각되는 조소상이

요가 수행자의 자세를 취한 채 발견된 바 있다

(Mirceal Eliade, Yoga: Immortality and Freedon Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1971).

그러나 요가의 시작이 어디서 왔는지와 별개로,

요가라는 수행법이 내용과 형식을 제대로 갖추어

비로소 요가의 역사를 써내리기 시작한 것은 우빠니쌰드 시대이다.

요가라는 명칭의 행법으로 사용되고,

체계화된 시기는 불교 발생 이전으로 생각된다.

까따 우빠니쌰드는

요가에 대해 '모든 심리기관을 굳게 집지(執持)하는 것'이라고 말한다.

따읻뜨리야 우빠니쌰드에서는

요가를 인간의 몸으로 나타내 여러 부위를 특정한 행법의 의미로 표현하여 설명한다.

바가와드-기따에서는 요가를 평정하는 것이라고 정의한다.

빠딴잘리의 '요가 쑤뜨라'에서는 요가를 심작용의 소멸이라고 정의한다.

콕 집어 정확히 언제 요가가 하나의 철학 학파가 되었다고 말할 수는 없으나,

4세기 무렵 빠딴잘리의 '요가 쑤뜨라'는

요가에 대해 이론-실천 양 측면에서 가장 체계적이고 권위 있는 최초의 저작으로 알려져 있다.

이후 '요가 쑤뜨라'에서 소개한

8가지 요가 행법이 하나의 학파로서 자리를 잡고,

인도인들에게 전승되어 온다.

이러한 요가에 대한 해설은 현대까지도 그 역사가 이어오고 있다.

1.1. 요가의 역사적 개요[편집]

베다 경전은 힌두교에서 받드는 네 가지 경전을 말하며,

그중에서도 리그베다가 가장 먼저 쓰여졌고 가장 큰 영향력을 끼친다.

이러한 베다의 신성성은 힌두교의 근본이라 해도 좋겠는데,

이른바 슈루띠라 하여 이러한 베다는

높은 경지에 이른 수행자가 신에 의해 계시를 받아 사용한 것이므로

시간과 공간을 초월하고 불변하며 절대적인 진리의 성격을 띤다.

이러한 것과 반대되게 인간이 개입하여 쓴 내용을 스므리띠라 한다.

베다 경전에 네 가지가 존재하는 것 외에도

그 네 가지는 각각 네 부분을 가지는데,

그중에서도 마지막 부분이 우파니샤드이다.

우파니샤드는 사색서라고도 불리며,

유일실존하는 브라만과 개별적 자아인 아트만과의 관계에 대해 생각하는 경구들이다.

우파니샤드 시대란

즉 이러한 우파니샤드가 쓰인 시대이다.

북부 인도에서 기원전 10세기경 철기 시대가 시작되었고,

이후 늘어나는 철제 기구의 사용과

그에 따른 농경 생산력,

인구의 증가 등은 기원전 6세기경 도시화 시대를 불러온다.

물

질적 풍요로 말미암아 정신적으로 사색하는 사람들이 늘어갔고,

특히 힌두교로 탈태하기 이전 베다의 영향 아래 희생제의로 바쳐지는 소들과

늘어나는 상인 계층의 영향력은 새로운 사상의 등장을 요구했다.

이때 등장한 것이 그 유명한 불교,

그리고 자이나교이다.

이후 이들,

특히 불교는 힌두교와 오랜 싸움을 벌이게 된다.

앞서 말한 제반 과정 및

이러한 경쟁 속에서 많은 철학들이 등장하였는데,

요가는 이 중 힌두 측에 서서

사상적인 면이 아닌 수행적인 면을 담당했던 철학 사상이다.

심지어는 부처조차도 본래 요가 수행자였다!

수행적인 면을 담당한다는 뜻은

요가가 어떤 사색적 고찰로 신에 이르는 방법을 논한다기보다 수

행세계에서 가져야 할 명상의 도리 등을 논한다는 뜻이다.

근본적으로 요가의 사상 체계는

그 기초를 상키야(Sāṅkhya, 數論) 철학에 둔다.

그러나 세계관의 많은 것을 빌려왔을 뿐 둘

은 다른 철학임을 잊어서는 안 되며,

요가는 상키야 철학이 아닌

여러 철학에서 포섭하였던 수행 방법임을 명심해야 한다.

애초에 상키야 철학은

무신론을 논하고 요가는 유신론을 논한다.

수행자에 따라 다르기는 했겠지만.

즉,

정리하자면 요가는

인도에 존재하는 많은 철학들이 수

행세계에서 신에게 어떻게 하면 다가갈 수 있는가를 논하며 실천했던 수행 방법이며,

그 공통점을 꼽자면 지

극한 명상의 경지에 이르기 위한 수도라고 할 수 있다.

요가 철학에 따르면,

당신이 요가의 고수라면 무종삼매의 경지에 이르러 해탈할 수도 있을 것이다!

1.2. 요가 철학의 형이상학[편집]

요가는 세계관의 많은 부분을 상키야 철학에서 빌려온다.

상키야에 의하면,

세계는 다수의 '뿌루샤'와 단일한 '쁘라끄리띠'로 이루어져 있다.

뿌루샤는 영혼이나 자아 따위로 생각할 수 있으나 정확하게 대응하지는 않는다.

사람은 죽으면 어디로 가는가?

상키야에 따르면 뿌루샤는 불변한다.

뿌루샤는 시간과 공간을 초월하며,

항상 편재하는 존재이고,

불멸한다.

즉 상키야에 따르면

인간은 이러한 뿌루샤의 성질을 깨닫지 못하기 때문에 잘

못을 빚어내는 것으로,

뿌루샤의 본질을 직관하고

자아의 완전성을 깨닫는 순간 해탈한다는 것이다.

이로써 영혼에 대한 의문을 해결하고나자,

철학자들에게는 세계에 대한 의문이 남았다.

생각건대,

작은 천 조각을 찢으면 더 작은 천 조각이 있고

그보다 더 작은 조각이 있을 것이다.

결국 눈에 안 보이게 찢어도

그곳에 미세한 무언가가 있다는 것은 분명하다.

그렇다면 그것보다 더 미세한 것은?

이 세상은 과연 무엇으로 이루어져 있는가?

그것은 우리가 지각할 수 있는 존재인가?

우리의 지각은 무엇으로부터 비롯하였는가?

상상할 수 있는 모든 개념을 미분하고 나면

그곳에는 이제 바로 세계의 본질이 남는다.

그 본질이란 쁘라끄리띠이다.

이 세계는 바로 이러한 쁘라끄리띠의 전개로 말미암아 이룩되었던 것이다.

뿌루샤를 제외하고 나면 쁘라끄리띠만이 남는다.

예컨대 누군가 지금 글귀를 쓰는 중에 있다면,

글을 작성하는 그 생각의 조각조차도

쁘라끄리띠의 영향 아래에 있다.

그의 생각은 불완전할 것이지만,

그의 뿌루샤는 완전할 것이기 때문이다.

불완전한 모든 것은 쁘라끄리띠이고,

쁘라끄리띠의 전개 중에 있다.

따라서 불완전한 '나'를 포함한 모든 세계의 객체는

쁘라끄리띠가 전개되어가는 모습이다.

그러므로 이러한 추리가 가능하다.

뿌루샤가 불변한다면,

쁘라끄리띠는 영변할 것이리라.

그렇다면 어떻게 하여 그러한 변화의 양태를 지닐 것인가?

상상할 수 있는 세 가지 성질

ㅡ 즉 쁘라끄리띠는 삿뜨바,

라자스,

따마스의 속성을 가진다.

삿뜨바란 밝고 경쾌하고 즐거운 성질이다.

예컨대 신에 대한 찬가를 부를 때 떠오르는 즐거운 상념이 삿뜨바를 띨 것이다.

라자스는 역동적이고 격정적이며 고통스러운 성질이다.

따마스는 무겁고 어두운 성질이다.

세계의 모든 것은 이 세 속성 중

어느 속성이 더 많은 비중을 차지하느냐로 결정된다.

어떻게?

쁘라끄리띠는 이러한 세 성질이 균형을 이루고 있는 상태이기 때문이다.

뿌루샤가 쁘라끄리띠와 접촉하면

라자스가 동요하면서 세 속성이 우위를 차지하게 된 각축을 벌이게 되고,

인간 존재를 해명하는 일련의 전개 과정이 나타난다.

이 과정에서

몸이나 마음, 이성, 자아 의식 따위가 태어난다.

한 마디로 몸이나 마음,

나를 나라고 생각하는 자아 의식

즉 아항까라조차도 쁘라끄리띠의 일부인 것이다.

말했듯이 뿌루샤만이 불변하는 존재이다.

그렇다면 불변하는 뿌루샤의 참모습을 제대로 보려면 어떻게 해야 하는가?

뿌루샤를 비추어볼 수 있는 거울인 찟따를 정결하게 하고 동요치 않도록 해야 한다.

그러한 방법이 바로 요가이다.

1.3. 요가 수행의 이론[편집]

요가의 목적은 쁘라끄리띠의 속박으로부터 인간을 해방시키는 인식을 획득하는 것이다.

자아가 쁘라끄리띠로부터 절대적으로 독립되어 있다는 인식을 통해,

자아를 정신작용과 동일시하는 무지와 착각에서 벗어나 뿌루샤로서 참된 자아가 드러난다.

요가에서는 이러한 일련의 수행에서 다음과 같은 개념을 논한다.

찟따브리띠는 잔잔한 수면에 이는 물결과 같이 찟따에 이는 작용이다.

찟따는 자아와 별개의 존재이다.

찟따는 빠딴잘리에 의하면 붓디(고통),

마나스(마음),

아항까라(자아의식)의 복합체인 내적 기관이다.

요가 수행은 바로 이 찟따를 통제하기 위한 수행론이다.

혼동되는 정신 작용,

찟따브리띠를 소멸시키고 자아가 찟따와 분별되도록 해야 한다.

이러한 통제는 빠딴잘리에 의하면 여덟 단계가 있다.

각기 금계의 야마,

권계의 니야마,

좌법의 아싸나,

조식법의 쁘라나야마,

제감의 쁘라땨하라인 다섯 가지 하타 요가와 응념의 드하라나,

정려의 드야나,

삼매의 싸마디인 세 가지 라자 요가이다.

1.3.1. 요가에서 말하는 삶의 단계[편집]

찟따는 삿뜨바,

라자스,

따마스의 뜨리구나로 구성되어 있으며,

이 뜨리구나 중 어느 요소가 강세를 띠느냐에 따라 정신적 삶의 수준이 나뉜다.

요가는 정신적 삶의 수준을 다섯 가지로 구분한다.

각각의 상태는 또 다른 상태와 상호 작용한다.

예컨대 사랑과 증오는 서로 대립하며 상쇄되는 감정이다.

요가는 마음의 모든 단계에서 얻어지지 않으며,

마지막 두 단계만이 요가의 수행에 유효하다.

끄쉽따,

동요는 라자쓰와 따마쓰의 지배 하에 있는 상태로,

감각대상에 관심을 갖고 있고 힘을 달성하는 수단에 매혹 당하고 있다.

황금이나 권력 등 세속적 대상을 쫓는 상태로,

어느 대상에 대한 신뢰를 가지지 못한 채 다른 대상에 대한 관심으로 옮아간다.

마음과 감각이 제어되지 않는 상태인 것이다.

무다,

무감각은 아직 따마쓰의 속성이 강한 상태로 악마나 홀린 사람의 마음과 같다.

즉,

무지나 수면,

악과 같은 상태이다.

빅쉽따,

산란은 따마쓰의 지배로부터 자유로워지고 오로지 라자쓰와 접촉하는 상태이다.

어떤 대상에 대해 마음을 잠정적으로 집중하고 모든 대상을 명료하게 인식할 수 있는 능력이 있으며,

덕성과 지식 등을 강화해나가는 상태이다.

그러나 이것 역시 정신적으로 산란한 상태로,

요가라 부르지 않는다.

왜냐하면 알아나간다는 것은

무지에서 비롯된 고뇌가 소멸되지 않아

정신 작용을 계속해나간다는 것을 뜻하기 때문이다.

에까그라,

전념은 라자쓰의 불순함이 정화된 상태이고,

삿뜨바의 완벽한 표현이다.

정해진 대상에 대해 램프의 불꽃처럼 흔들리지 않는 마음의 상태로 집중할 수 있으며,

비로소 찟따브리띠를 소멸하기 위한 방법을 마련한 것이다.

마음의 지속적 집중이 가능해야 뿌루샤를 드러낼 수 있기 때문이다.

그러나 어떤 대상에 대한 명상을 계속한다는 것

역시 찟따브리띠에 속하므로 심리과정은 아직 단절되지 않았다.

니로다,

소멸은 이전 단계의 정신 집중을 포함한 모든 정신 기능의 정지이다.

일련의 찟따브리띠가 완전히 제어되는 상태이고,

이 상태에서 찟따는 평온과 평정의 원시적 상태로 남는다.

마지막 두 단계는 요가에 도움이 되는 정신의 단계로,

이 단계에서의 명상을 '싸마디'라고 달리하여 부른다.

무협지나 불경에서 많이 들어보았을

삼매라는 단어가 싸마디의 한역이다.

싸마디는 빠딴잘리가 소개한

요가의 여덟 가지 행법 중 마지막의 것으로,

결국 앞의 일곱 가지는

이 싸마디에 도달하기 위해 있는 것이라고 해도 틀리지 않다.

1.3.2. 싸마디[편집]

요가 행법에 의하면 싸마디는 드하라나,

드야나,

싸마디의 세 단계를 거친다.

드하라나는 한정된 대상에 마음을 제한하여 응념하는 것이고,

드야나는 그런 대상을 향한 마음의 흐름이 차분하게 정려한 것이다.

즉,

일상적 사고에서는 마음이 끊임없이 한 대상에서 다른 대상으로 이동하고자 하는데

드하라나는 그런 빈도가 드물어지며,

드야나에서는 그런 일이 없다.

드하라나와 드야나를 거치면

결국 대상과 수행자 간에는 단 하나의 교란만이 남게 되는데

그것은 바로 수행자의 자아 의식이다.

"명상의 대상에만 의식이 있고 그 자체에는 없을 때 그것을 삼매라 한다."

라고 요가 수뜨라는 싸마디를 설명했다.

대상을 갖는 싸마디를 유종삼매,

쌈쁘라갸따 싸마디라 한다.

그리고 마음이 고요해진 상태인 끄시빠브리띠에서

인식의 주체가 대상에 대해 머무르는 것을 특히 싸마빠띠,

등지삼매라 이른다.

찟따가 신이나 성상 등 외적 세계의 거대한 물질적 대상에 전적인 집중이 될 때,

어떤 표식을 통해 진체에 접근하는 등지삼매를 싸비따르까-싸마디라 하고,

표식을 동반하지 않는 것을 니르비따르까-싸마디라 한다.

딴마뜨라(우주를 구성하는 극대 원소) 등 미세한 대상들에 대해 머무르는 등지삼매에 대해선,

표식을 동반하는 것을 싸비짜라-싸마디라 하고 동반하지 않는 것을 니르비짜라-싸마디라 한다.

표식의 동반에 대해서는 지표와 표의의 관계를 생각해보면 쉬울 것이다.

이러한 유상삼매의 단계는 싸난디 싸마디,

환희삼매의 단계를 지나쳐서 싸스미따 싸마디,

자기의식 삼매에 다다른다.

유종삼매의 다음에는

대상이 없는 삼매인 무종삼매가 있는데

이를 아쌈쁘라갸따 싸마디라 한다.

이것이 싸마디의 최종 단계이다.

그러나 자아가 삼매의 상태에 도달하여 고통으로부터 자유로워진다 하더라도,

현재와 과거에 기인한 마음의 습은 남는다.

습이라고?

그러나 인도 철학에 의하면,

생각조차도 인과에 얽매여 있으며,

그 흔적을 남긴다.

어떤 행위조차도 업에서 자유로울 수 없는 것이다.

따라서 삼매의 상태에서 꾸준히 자신을 지키고,

현재의 과거에 대한 여러 종류의 까르마를 소멸하기 위해 지속적인 노력을 필요로 한다.

참고로 행위 이후에 남는 그 씨앗을 쌍스카라라 하고,

쌍스카라 중 와싸나로 남는 것이 쓰므리띠,

기억으로 전환된다.

쓰므리띠가 동인이 되어 다시 쁘라끄리띠,

행위가 발원한다.

2. 요가의 종류[편집]

매우 긴 역사를 가지고 있는만큼 유파도 다양하고 스승과 제자,

또 유파간의 대립이나 교류 등으로 인해

그 세세한 종류를 따진다면 매우 방대하지만

일단 수행방법의 원류인 힌두교의 전통에서는 요가를 여섯가지로 구분한다.

라자요가,

하타요가,

갸나요가,

박티요가,

카르마요가,

만트라 요가가 그것이다.

그 외에도 실천의 방법에 따라서 나다 요가,

쿤달리니 요가 등의 명칭들이 있으나

일단은 크게 위의 여섯가지를 종류라고 구분하며

나머지는 유파간의 실천방법론에 따라 달리 부른다.

현대인들이 가장 쉽게 접하고 생각하는 요가는 저 위의 여섯가지 중 하타 요가이다.

하타 요가는 '''음과 양의 에너지를 조화롭게 하다"'(하-양:해, 타-음:달) 라는 뜻이다.

그래서 현대에는 요가의 정신적인 내용 수행 등은 상당히 배제되고

요가의 동작들을 이용한 다이어트의 일종으로 전세계에서 각광받고 있다.

미국의 팝 가수 마돈나 등도 요가 예찬론자.

또 몸을 도구 삼아 수련을 하다보니 다이어트 외에도 재활운동 쪽으로 상당히 강력한 효과를 가지고 있다.

아서 부어맨(Arthur D. Boorman)의 요가 재활 이야기를 들어보자.

사실 저 사례는 DDP 요가다.

일반 요가와는 확연히 다르니 혹시라도 그냥 요가로 저렇게 살뺄 생각은 하지 말자.

뺄수는 있어도[4] 저렇게 단기간에 뺄수는 없다.

DDP 요가에 식단조절이 들어가있기 때문에 할 수 있는 것.

특이한 사례로,

2010년부터는 미군의 훈련 프로그램에서도 요가 과목이 들어가 있다.

병사들의 육체적 능력을 향상시키고

야전에서 겪는 정신적 스트레스를 경감시키는데 도움을 줄 수 있다는 이유이다.

2.1. 아쉬탕가 요가(Ashtanga Yoga)[편집]

아쉬탕가 빈야사 요가(Ashitanga Vinyasa Yoga)의 줄임말이며

인도의 요가 스승 슈리 티루말라이 크리슈나마차리야(1888-1989)와

그의 제자 파타비 조이스(1915-2009)가 1948년 창안했으며 클

래식한 요가 스타일인 '아쉬탕가'는 '8단계'라는 뜻으로

요가 수트라의 수련 방법을 충실히 따르는 수련법 중의 하나다.

요가 수트라는 BC200년경 인도의 위대한 현자인 Pantanjali가 쓴 책으로

파탄잘리는 이 책에서 아쉬탕가 요가를 설명하는데 아

쉬탕가란 8개의 가지(단계)라는 뜻을 담고 있다.

아쉬탕가 요가의 핵심은 우짜이 호흡,

반다(잠금),

빈야사(흐름),

드리슈티(응시)를 포함하며 아쉬탕가 수련은 몸과 마음을 강화시켜주는

매우 단단하고 남성적인 느낌이 묻어나는 수련법 중의 하나이기도 하다.

파탄잘리는 기존의 요가가 매우 정적인 면이었던 것을

아사나와 함께 수련하여 요가의 체계를 잡았다고 평가받는다.

다른 요가와 달리 동작의 순서(시퀀스)가 정해져있으며,

이 시퀀스는 초급, 중급, 고급으로 레벨별 차이가 뚜렷하게 구분되는 특징도 있다.

아쉬탕가는 시퀀스 시리즈들의 세트로 구성되어 있다.

수련 시퀀스는 세부적으로는 수리야(Surya Namaskara),

스탠딩(Standing)[5],

시팅(Seating),

백벤딩(Back-bending)

피니싱(Finishing) 시퀀스로 다시 나눌 수 있다.

일반적으로 수리야,

스탠딩,

백벤딩,

피니싱은 기본적으로 모든 단계에서 수련하고,

중간에 시팅 시퀀스를 하느냐 세컨 시퀀스를 하느냐에 따라

아쉬탕가 요가의 난이도가 결정된다.

초급은 프라이머리 시리즈(Primary Series)로 불리우며,

이를 다시 하프(Half)와 풀(Full) 시리즈로 구분한다.

프라이머리 시리즈는 스탠딩 시퀀스 이후 시팅 시퀀스를 수행하며,

시팅시퀀스 중 나바나사(보트자세)까지 하는 것이 일반적인 하프 시리즈이다.

일반적으로 아쉬탕가를 처음 하는 초보들은 하프시리즈까지 수련하며,

하프시리즈들의 모든 자세들이 완성이 되면 그 다음 풀 시리즈 진도를 나가게 된다.

풀 시리즈까지 완성이 되면 지도자의 지도 아래

세컨(중급), 어드밴스(고급)[6] 진도를 차례차례 나가게 된다.

실제로 어드밴스까지 진도를 나가는데

일반적으로 10년 정도 걸린다고 보며,

우리나라에서도 어드밴스를 수련하는 사람은 손에 꼽는다.

마돈나[7],

기네스 펠트로 등 헐리우드 스타[8]는 물론

우리나라에서는 이효리,

일본에서는 야노 시호가 수련하는 요가로도 잘 알려져 있다.

아쉬탕가는 수련 동작들이 정해져있다는 특징 때문에

다른 요가에는 없는 마이소르[9]이라는 특이한 수업방식이 존재한다.

지도자의 구령 없이,

본인의 진도에 맞게 수련을 하고 있으면,

지도자가 돌아다니면서 수련자들을 지도하는 방식이다.

수련자들은 자신의 몸 상태에 따라 강도나 호흡 시간 등을 조절 할 수 있다는 장점이 있고,

지도자들은 수련자들을 개인 PT 하듯 학생들을 꼼꼼하게 지도해줄 수 있는 장점이 있다.

이러한 장점 때문에 효율적인 요가 수련이 가능하지만,

어느 정도 시퀀스를 숙지하고 있어야 보다 효율적으로

마이솔 수련이 가능하기 때문에

일반 수업을 한 달정도라도 먼저 수강 후 듣는 것을 권한다.[10]

아쉬탕가의 창시자 중 한 명인 파타비 조이스가

여자 제자들을 가르칠 때 성추행을 했다는 주장이 나왔다.

파티비 조이스의 아쉬탕가 요가 계승자이자 손자인 샤랏 조이스는

성추행 혐의를 인정하고 사과하였다.

2.2. 아헹가 요가(Iyengar Yoga)[편집]

아헹가 요가는 창시자 B.K.S.

Iyengar에 의해 인도 푸네에서 시작된 요가이며,

해부학적인 면에 치중하며 블록이나 스텝 같은 도구를 사용한다.

동작 하나 하나마다 유지 시간이 길고 난이도도 높은 편이다.

또한 동작이 연결되기보다는 딱딱 끊어지는 것이 특징이다.

부상을 방지하고 안전한 동작을 위해 정렬,

정확성,

도구에 중요도를 둔다.

남녀노소 모두에게 적용 가능한 범용 요가로

척추 질환이나 불균형한 자세를 개선하기 위한 목적으로는 가장 좋은 요가로 알려져 있다.

회복요가(Restorative yoga)로도 알려져있다.

아헹가 요가의 창시자인 B.K.S.

아헹가는 크리슈나마차리아의 처남으로 알려져있다.

크리슈나마차리아가 전국에 요가를 전파하기 위해 집을 떠날 때,

인도의 전통에 따라 집안을 지키는 남자를 두어야 하는데,

처남인 아헹가가 너무 병약하여 직접 그에게 요가를 가르쳤다고 한다.

이러한 독특한 시작 덕분에 아헹가 요가는 신체 질병의 치료나 회복을 중심으로 수련하며,

이를 위해 소도구를 적극적으로 사용한다는 것이 다른 요가들과 뚜렷하게 구분되는 특징이다.

아헹가는 요가디피카(Light on yoga)라는 책을 1966년 출간하였고,

세계적 베스트셀러가 되었다.

현재도 이 책은 전 세계의 요가 수련자들에게 필독서[11]처럼 읽혀지는 책 중 하나이다.

이 책은 이론 위주로 서술되어 있으므로,

초보자는 BKS Iyengar Yoga라는 책을 많이 보는 편이다.

최근에는 개정판이 나와 있고 한국에도 번역되어 있다.

2.3. 빈야사 요가(Vinyasa Yoga)[편집]

빈야사 요가는 근력을 요구하는 아쉬탕가 요가,

균형을 중시하는 아헹가 요가,

개인 맞춤형 비니 요가의 장점들을 모아서 1990년대에 미국에서 만들어진 요가이다.

비크람 요가와 더불어 아메리칸 스타일이라고 불리우는데 아쉬탕가 빈야사 요가로부터 파생되었다.

빈야사는 원래 아쉬탕가의 목표자세를 완성시키기 위해 사전에 취하는 사전 준비 동작이었다.

빈야사는 아쉬탕가 아사나(자세, 동작)를 기반으로

호흡과 아사나를 끊임없이 일치시키며 물 흐르듯 연결하여 수행하는 요가이다.

움직이는 명상이라고도 불린다.

전신을 골고루 모두 쓰고 각 동작들을 연결하는 모습이 마치 춤을 추는 듯한 움직임을 가지고 있다.

아쉬탕가 빈야사 요가는 순서가 정해져 있지만,

빈야사 요가는 순서가 정해져 있지 않다.

하지만 그 변화 안에 분명한 규칙이 존재하고 체계적인 규칙안에 반복된 힘으로 요가를 수행함을 일컫는다.

2.4. 비크람 요가(Bikram Yoga)[편집]

비크람 요가는 국내에서 핫 요가(Hot Yoga)라고도 불리우는데

요가의 수많은 동작 중 26가지 동작으로 구성되어 있으며

대충 90분 정도의 시간을 소요하며 수련하는데

이 요가를 고안한 인도 출신의 운동 선수이자

요가 전문가인 비크람 코더리가 무릎부상에서 재활하기 위해서 고안한 동작들이다.

높은 온도에서 땀을 쭉 내는 스타일이 큰 특징이며 따라서 심장이나 혈압 등을 주의해서 수련해야 한다.

하지만 2013년 중반 비크람 요가의 창시자로 알려졌던 비크람 코더리가

수십년간 자신의 여제자들을 지속적으로 추행 및 강간했다는 것이 폭로되었다.#

최소한 6명의 피해자들이 공개적으로 미디어에 나와서 증언을 하였다.

심지어 비크람은 이 폭로가 나온뒤에 대책을 논의하던 자신의 여성법률고문조차 성추행할려고 시도했고,

그녀가 단호하게 거부하자 곧바로 해고하였다.

그

리고 전 법률고문이 부당해고 및 성차별 혐의로 피해보상 민사소송을 걸었고,

미국 법원은 비크람이 악의적이고 억압적으로 사기 행각을 벌였다는 판결을 내렸다.

비크람은 성추문과 관련한 6건의 민사소송에서 모조리 패소하였다.

게다가 이 과정에서 인도 요가 챔피언,

닉슨 대통령 요가치료 등 비크람이 수십년간 떠벌리고 다녔던

모든 과거 경력이 거짓이란게 드러났다.

심지어 비크람이 자신이 만들었다고 홍보해온 26가지 동작조차도

사실은 이미 인도에 존재하던 것이며,

비크람이 창시한게 아니라는게 드러났다.

비크람은 모든 재판에서 패소하자 공개활동을 중단하고

곧바로 도망치듯 미국을 떠나서 한동안 은신하다가

2018년부터 멕시코와 인도,

스페인 등 세계를 오가면서 공개적으로 활동하고 있다.

미국 전역의 비크람 요가 지부는 여전히 전처럼 비크람에게 여성교육생들을 보내고 있다.

모든 과정은 2019년 넷플릭스 오리지날 다큐멘터리 <비크람 - 요가 구루의 두 얼굴>

(Bikram-Yogi, Guru, Predator)에 담겨있다.

다만 해당 다큐에 출연한 피해자들은

비크람 요가가 자신의 건강에 도움이 되었다는 사실은 인정했으며,

앞으로도 요가를 계속 주변에 전파할 것이라고 이야기한다.

2.5. 테라피 요가(Therapy Yoga)[편집]

인도 전통 의학인 아유르베다를 접목한 것으로 수련자의 맥박을 짚고 몸 상태를 살핀다.

또한 정신적인 기운도 고려해 개개인의 특별한 상태에 적합한 동작,

호흡법, 명상 등을 처방하는 요가다.

일종의 맞춤 요가라 할 수 있으며 따라서 1:1 교습으로 진행되는 것이 일반적이다.

비니 요가(Vini Yoga)라고도 한다.

힐링요가와는 다르다

2.6. DDP 요가(DDP Yoga)[편집]

It ain't your mama's yoga.

니네 엄마가 하는 그 요가 아니다.

창시자는 前 WCW, WWE 프로레슬러인 다이아몬드 댈러스 페이지.

요가 동작에 다이나믹 레지스턴스(Dynamic Resistance)라고 하는 근력 운동 원리를 추가하여 운동 효과를 높였다.

기존 요가의 정신 수련 방법과는 단절되어 있으며

오히려 댄디하고 마초적인 미국적 이미지들이 곳곳에서 눈에 띈다.

이를테면 가장 많이 하는 스트레칭 동작인

다이아몬드 커터를 할 때의 기합소리인 Hulk it up~!이라던가.

뭔가 B급 냄새 풍기는 이런 독특한 노선으로 레슬링 덕후들이나

각종 너드들의 지지를 받고 있는 듯.

용어에 있어서도 기존 요가와 많이 다르다.

이를테면

전사 자세 → Road Warrior

비둘기 자세 → Can Opener

까마귀 자세 → Black Crow

아기 자세 → Safety Zone

이렇게 요가에 대한 자세에 있어서는 논란이 분분하지만 운동 효과에 있어서만큼은 인정을 받고 있으며

특히 WWE와의 커넥션이 홍보에 많은 도움을 주고 있다.

DDP Yoga는 각종 전현직 레슬러들의 재활에 이용되고 있으며 여기서 도움을 얻은 유명 레슬러들이

다시 DDP의 열렬한 지지자가 되어 자발적으로 홍보를 돕고 있는 것.

특히 앞에서 언급한 아서 부어맨의 재활기가 유명하다.

DDP Yoga의 운동 프로그램은 프렌차이즈 도장 운영보다는 DVD를 통한 홈 트레이닝으로 보급되고 있기 때문에

국내에서는 온라인 커뮤니티들을 중심으로 상당한 관심을 얻고 있으며

수련자들은 적지만 꾸준히 늘어나고 있는 중.

물론 복돌이 유저의 비율은...

2015년 12월에는 무료 앱도 나왔다.

2.7. 플라잉 요가(Anti gravity Yoga,

Aerial Yoga)[편집]

대한민국에서는 2010년대 중엽부터

유명 여성 연예인들이 한다느니 어쩌니 하는 입소문을 타고 조금씩 퍼지고 있다.[12]

말 그대로 해먹이나 고무끈,

기타 신축성 있는 소재의 구조물을 가지고

하늘에 대롱대롱 매달려서 중력을 이용하여 요가를 하는 것.

마치 발레나 체조와도 유사한 동작을 취하기도 하지만,

종종 거꾸로 매달리기도 한다.(…)

홍보 사진에 나오는 늘씬한 사람들은

느긋하게 미소지으며 요가를 하기에 방심하기 쉽지만,

이들은 숙련자이기에 웃을 수 있는 것이다.

처음 하는 사람이라면 생각보다 높은 난이도에 절로 비명을 지르게 된다고 (…)

사실 플라잉요가의 난이도 자체가 높은 것은 아니다.

해먹의 용도가 난이도 높은 자세들을 쉽게 할 수 있도록 도와주는 역할이고,

플라잉(즉,

떠있는) 자세의 목적이 바닥에 몸이 닿고서는 하기 어려운 스트레칭을 해먹을 이용하여 해 주는 것이기 때문에

다른 요가에 비하여 난이도가 더 높다고 볼 수는 없다.

다만 매달렸을 때 해먹에 달린 부위가 강하게(!) 조여지기 때문에

부위가 뭉쳐있거나 하는 경우에는 통증을 느낄 수 있다.

사극에서 주리를 틀 때 죄수가 비명을 지르는 원리와 동일하다(...).

사극에서는 간수가 막대기로 비트는 힘으로 받는 고통이라면 플라잉요가에서는,

해먹에 걸쳐진 자신의 체중이다.

매트 위에서 해먹을 이용하여 몸 여러 부위를 스트레칭을 해 준다.

해먹에 손과 발을 걸어준 후 몸을 여러 자세로 비틀어 주어 몸을 풀어 주고 해먹에 매달려서 여러 가지 동작들을 실행한다.

해먹의 도움을 받기 때문에 일반적으로는 불가능한 자세들도 쉽게(?) 행할 수 있다.

특히 해먹에 거꾸로 매달리면 중력에 의하여 관절 부위가 이완이 됨으로 허리통증,

어깨통증 등에 좋은 효과를 볼 수 있다.

병원에서 실시하는 물리치료 자체가 관절과 관절을 이완 시키는 작용인데 해먹에 매달리는 자세를 취하게 되면

강렬한 이완효과로 허리/어깨통증 완화에 큰 효과를 볼 수 있다.

단,

지구가 당기는 자신의 체중이 해먹에 묶인 신체 한 부위에 걸리기 때문에 처음 시도하게 되면

원래 가지고 있던 허리통증,어깨통증보다 훨씬 더 큰 통증을 맛 보게 될 것이다(...).

기본적으로 유연성과 근력을 필요로 하는 운동이지만,

무엇보다 겁이 없어야 한다(!) 고소공포증이 있는 사람들에겐 권장되지 않으며,

머리 위치가 계속 상하좌우로 바뀌다보니 멀미가 나기 쉬워 플라잉요가 4시간 전에 식사를 마치는 것이 좋다.

전신근력운동이라 전체적인 신체의 근육을 다듬는 데에 좋고,

신체말단을 해먹으로 쥐어짜거나 긁어내는 동작이 많아 셀룰라이트를 제거하는데 도움이 된다.

초보자 팁은 해먹을 신체에 묶는 자세를 할 시 해먹이 뭉치지않게 해야한다.

그리고 피가 안 통한다고 겁먹을 필요는 없다.

다리,

팔 등이 감각이 잠깐 사라지는것 뿐이다.

비슷한 것으로 '번지 피지오'가 있다.[13]

3.

요가와 불교[편집]

요가는 과거 인도의 힌두교 수행의 방법이다.

당연히 당시 수행자였던 부처는 요가를 수행했고,

경지에 올랐다고 표현되고 있다.

무슨 말이냐면,

당시 인도에서 수행한다고 나섰으면 요가를 하는거라고 보면 된다.

즉 불경에서 '싯달타가 명상,

수행했다'라는 말이 나오면 그걸 그냥 요가했다라고 봐도 된다.

물론 싯달타는 힌두교 철학이나 여타 요가 스승들의 가르침에서 따로 나아갔으며

신체 수행에 집중하는 경향을 피하게 된지라 요가에서 떨어져 나온 셈이며,

현재는 호흡법과 정신조절에만 요가의 형태가 남아 있다.

상세하게 보자면 현재 불교의 호흡법은 싯달타의 새로운 어레인지 호흡법이라고 생각하면 된다.

즉,

고대 인도 기준으로는 불교는 싯달타라는 스승이 세운 새로운 요가라고 봐도 되는 셈이다.

인도에선 모든 무술의 원류가 요가에서 나온다고 여기는 이들도 많이 보이기도 한다.

극진공수도의 최영의 총재도 무술의 요가 기원설에 대해서 이야기하기도 했다.

특히 소림사와 선종을 창시한 사람이 인도인 승려 달마라는 점은 중국인들에게 굴욕과 같은 상징이라

애써 중국에선 다인종이 모여 살았기에

인도계 귀화 중국인이라고 요가와 무관함을 주장하기도 한다.

그러니까 그 달마가 인도계 귀화 중국인이라는 것.

하지만 문제는 이 달마가 실존 인물일 가능성이 낮다는 것.

달마, 소림사 문서로.

최근에는 그냥 황제내경을 기원으로 해 중국 내에도 자체적인 기공의 영역이 있었으며

그것을 화타가 집대성해서 오금희로 만들었다고 주장하며 요가와 차별화하기도 한다.

무술의 원류가 요가라기보다는 아시아 무술들이 칼라리 파야트의 영향을 받았고,

이 칼라리 파야트는 칼라리라는 학교에서 수행자들이 배우던 과목 중의 하나였기 때문에 그렇다.

현재로서는 실존 달마라는 인물이 중국으로 넘어갔지는 않았어도

인도와 교류한 것 자체는 확실하기 때문에,

중국에서 이어지는 무술계보들은 인도 영향권이라고 볼 수 있다.

4. 요가와 스트레칭[편집]

요가 동작이 스트레칭 효과가 있는 건 맞다.

하지만 요가는 철학이고 정신수련이며 정신과 연결되어 있는 몸을 단련하여 마음을 제어하기 위한 동작이다.

즉 삼매,

해탈을 목표로 하고 있는 것이다.

이것은 불교 이전부터 인도에 있던 철학적인 관념이었다.

수천년 전 요가 수행자들이 요가를 의념을 양념으로 친 스트레칭으로 시작했을리가 있나(...).

외형적인 점이 스트레칭이랑 비슷하다고 '요가=스트레칭+의념'이라고 보는 것은

요가에 대한 이해를 못한 채 설명하는 것이다.

몸동작을 잘 하고 거기서 좀 자세하게 들어가면 의념을 배우고 그런게 아니라,

아예 정신을 조종하기 위해 몸을 움직이는 행위인 것이다.

명상을 한다 치면 아무리 초심자라도 정신 조절을 하겠다고 앉는 것이지,

앉고서 숨쉬기가 좀 잘 된다 싶으면 그 다음에 의념수련이란게 있는데요 하면서 설명해 주는 게 아닌 것과 같다.

5. 국가별 요가의 입지[편집]

5.1.

인도[편집]

세계적으로 요가는 다이어트와 스트레칭,

웰빙 등으로 인기를 끌고 있다.

반면 인도에서 요가란 나이 든 노인들이 하는 정신수행의으로 받아들이고 있다.

그리고 젊은 층에겐 구시대의 상징쯤으로 여겨지고 있는 모양.

과거 우리나라에서 스님들이 도술을 쓴다던가 하는 이미지가 있는 것과도 비슷하다.

의료 인프라가 열악한 시골에선 요가 구루들이 민간의료행위를 하는 경우가 많다.

인도가 IT 업계 등 최신 기술 쪽으로 발전하는 것을 보면 이해가 안되는 것도 아니다.

과거 한국의 산업화 시절에도 젊은 지식인들에겐 과거의 문화나 철학 등을 상당히 배제하던 것과 비슷하다.

쉽게 얘기하자면 갓쓰고 도포입고 유교경전이나 읊고 있는 시골 어르신을 바라보는 우리네의 시각과 비슷하다.

사실 무술 덕후들은 중국의 무술촌이나 일본의 고류 무술 유파에 대해서 환상을 가지고 있는 경우가 많지만

사실 중국이나 일본에서 그러한 무술가들은 역시나 갓쓰고 다니는 어르신들 같은 이미지일 뿐이다.

스포츠화된 산타나 검도(전검련)쪽이 훨씬 인기가 있는 것이 괜히 그런 것이 아니다.

그리고 첨단산업에 종사하는 세대들은 거진 나스라니 토마스 기독교나 시크교,

혹은 파르시(조로아스터교)인들이 대부분 이끌고 있기 때문이기도 하다.

한국에서도 전통문화를 천시하고 없애버리자고 하는 사람들 대다수가 개신교인들인 것과 지

금도 요가나 참선을 개신교인들이 색안경 끼고 본다는 걸 생각하면 된다.

물론 이것도 옛말이고 요새 비과학적인 전통적 요소들을 유사과학으로 강하게 비판하면서 없애야 할 것으로 보는 것은

과학적 회의주의자나 무신론자 계열들이 대부분이다.

한의학에 대한 태도를 보면 될듯.

요가도 따지자면 분명 엄밀한 의미에서 과학은 아닌데 요가는 워낙 세가 크고

적어도 신체활동적인 면에선[14] 경험적으로 그리고 실증적으로 증명이 많이 된 편이라서 잘 안 까는 듯...

5.2. 서구권[편집]

히피즘이 유행하던 60~70년대부터 인도에서 퍼져 서구권부터 유행하기 시작했다.

요가는 원래 인도 남성의 전유물이지만,

한국을 포함 세계적으론 여성들에게 더 어필하는 편이다.

히피즘과 함께 오리엔탈리즘의 일부로 동양의 신비한 정신수양법으로 알려지다가

2000년대 이 후론 정신수양의 의미는 많이 사라지고 건강을 위한 체조의 일종으로 바뀐 편.

우리나라를 포함한 서구권에선 여성 위주로 실내에서 매트 깔고 레깅스입고 하는 다이어트체조 정도의 의미로 통한다.

5.3. 한국의 요가[편집]

한국에 처음 들어온 건 의외로 늦어도 80년대 중후반으로 추정되는데,

당시의 드라마에 동네 주민센터에서 요가 수업을 듣는 여성도 등장했을 정도.

하지만 90년대까지 꽤 왜곡된 이미지로 많이 알려져있다.

공중부양이나 입에서 불을 쏘거나(...) 몸을 마구 꼬고 늘리고 하는요가파이어 이미지의 우스꽝스러운 모습.

한땐 컨토션 등도 그냥 요가라고 싸잡아서 부르기도 했다.

그러다가 본격적으로 유명해진 것은 2000년대 초를 기점으로 구미권에서 소비되던 미국식 다이어트 요가 등이 미디어를 통해 노출이 되기 시작하고

젊은 여성들을 중심으로 그런 미국식 다이어트 요가가 쿨한 운동으로 이미지메이킹을 하면서 부터.

티비에서 본격적으로 당시 편견에 가깝던 컨토션에 가까운 동작이 아닌

비교적 쉽고 운동에 효과적인 동작들과 함께 요가의 효능을 보이기 시작하면서다.

또 옥주현 등의 몸매 좋은 연예인들이 요가로 몸을 관리한다는 말이 돌기 시작하고,

제시카,

나디아 등 스타급 요가강사들이 언론에 등장하면서 더 붐을 타기 시작했다.

그로부터 십여년이 흐른 지금은 그래도 수준들이 상향평준화 되었다고 보는 것이 일반적인 시각이다.

정보가 부족하던 과거와는 달리 요즘은 마음만 먹는다면

세계적으로 권위있는 요가 마스터나 요가 단체로 직접 찾아가 배울 수 있는 여건이 되기 때문이다.

단기 연수로 양산된 실력없는 요가 강사들의 행태를 보다 못한

정의감 넘치는 일반인들이(...) 현실에 개탄해서 제대로 요가를 꾸준히 배우고

미국까지 다녀오면서 요가를 배워 지도자가 된 경우도 꽤나 많다.[15]

요가 스튜디오들도 심심치 않게 보이고,

일단 피트니스 클럽에서는 GX 수업의 필수 요소가 되었다.

단,

피트니스 클럽의 경우 여러가지 사정으로 제대로 요가를 배우기에는 아쉽다는 약점이 있다.

첫번째로 피트니스 클럽에서 활동하는 강사들은 아직 경력이 짧은 경우가 많고,

두번째로 어쩌면 가장 심각한 문제일 수 있는 것이 피트니스 클럽에서 하는 요가 수업은

대부분 수업 수강자가 꾸준히 바뀌는터라리셋 강사가 진도를 step by step으로 진행할 수가 없다.

실제로 꾸준히 요가수업에 참가하는 사람에게 강사가 요가 스튜디오를 추천해주는 경우도 있고...

더불어 비크람 요가 같은 경우는 38도의 온도를 유지하는 것이 기본 컨셉인데 일

반 피트니스 센터의 GX룸에 그런 장치가 있을리가...

요가 학원에 다니면 강사의 수준에 따라 다르지만 요가를 분파에 따라 나누어 놓기 때문에

요가를 좀 더 깊게 수련할 수 있으며 요가에 특화된 곳이니만큼

GX룸에 매트만 깔아놓고 하는 피트니스 클럽 요가보다 훨씬 편안한 환경에서 요가를 배울 수 있다.

최근에는 요가의 전통적인 수련 방법과 현대적인 방식을 접목시켜 근력 운동에 비중을 좀 더 주는 프로그램도 많아졌다.

어쨌든 최근에도 요가의 붐은 과거처럼 광적인 것은 아니더라도 꾸준히 지속되고 있고 그 안에서 실력이 없거나 게으른 자들은 자연도태되고 있다.

한국 사회가 건강한 사회를 지향하면서 양생법에 관심이 쏠리고 있는데,

한국에 존재하는 여러 기공단체는 대부분 정체불명이거나 요가에서 동작들을 따와서

제멋대로 개량하고는 배달민족 정통 수련법 이라는 되도 않는 개헛소리를 해대는 경우가 잦다.

반면 요가는 이미 단기연수의 폐해를 겪고 시간이 꽤 흐른데다 양생 방면으로

이미 제대로 검증된 경우이며 거짓말을 할 수 없기에 그

런 신뢰도 면에서 다른 정체불명의 사이비 기공,

양생단체와는 상대가 되지 않는다.

따라서 앞으로도 한국에서 양생,

건강법으로서 요가의 독보적인 인기는 계속될 듯 하다.

덤으로 요가는 정체불명 기공단체와는 달리 제사를 지내야 한다며 돈내라고 하지 않는다.

5.3.1.

그 외 양생 단체[편집]

한마디로 환빠,

유사과학자,

종교인,

장사꾼들이 많기 때문에 문제가 되는 것인데,

한국 고유 계열의 수행단체들이 전부 잘못된 것은 아니니 배워보고 싶다면 주의깊게 고르는 것이 좋다.

대체로 규모가 크고 역사가 오래 된 단체를 택하는 것이 좋지만,

가장 흔하게 볼 수 있는 단월드 계열은 종교적 색채를 띈 기업이므로(...) [16] 웬만하면 초보자는 입문을 삼가는 것이 좋다.

국선도 계열은 역사와 규모도 꽤 되고 나름 수련법이 체계적이면서 독자적이므로 무난한 선택이다.

최소한 종교적인 것을 강요하거나 일반 체육관 수준 이상으로 금품을 요구하지는 않는다.

선무도(금강영관) 계열은 특히 부산 쪽이면 접하기 쉽다.

다만 한국 불교의 성향상 다소 권위적으로 지도를 하게 되므로 거부감이 들 수도 있다.

(무협이나 불교영화같은데서 보여주듯 빗자루로 내리치며 일갈을 하는 노스님을 생각하면 된다(...)) [17]

이 둘의 경우에는 명상(혹은 참선)과 호흡법,

기공체조와 스트레칭,

신체단련 등을 종합적으로 한다.

즉 요가랑 거의 유사한 체계이다.

개신교계에선 두 가지 측면으로 바라본다.

첫 번째는 요가는 종교적인 내용이 포함되어 있기 때문에 하면 안된다는 입장이 있고

두 번째로 한국의 요가는 그런 종교적인 내용이 별로 없고 또 설령 정신 수양적 내용이 나오면

그냥 무시하고 운동에만 집중하면 된다는 입장이 있다.

대체로 그리 크게 뭐라 안하는 편.

사실 개신교를 떠나서 범기독교적으로 보수적인 곳에서는 요가를 부정적으로 보는 시선이 꽤 존재한다.

그래서 요가는 하고 싶은데 왠지 모르게 찝찝한 사람들을 위해서

크리스천 요가(?!) 학원같이 종교적인 내용을 배제한 요가학원도 존재한다.

2017년 9월을 기점으로,

대한예수교장로회 통합 측은 공식적으로 요가와 마술을 금지해야 한다는 보고서를 채택했다.

(관련기사)

5.3.2.

커플 유튜버들의 컨텐츠[편집]

2010년대 후반부터 커플 유튜버,

인터넷 방송 BJ/스트리머들을 중심으로 요가를 하나의 컨텐츠로 활용하고 있다.

대개 남녀가 밀착하는 요가 동작을 따라하는 식으로 진행된다.

6. 요가의 자세[편집]

이 문단은 요가 시에 사용되는 자세에 대해 기록되어 있습니다.

전사 자세

고양이 자세

코브라 자세

메뚜기 자세

활 자세

요가

요가

성동구영어 전문에서 빨리구하세요 - 과외팡팡

[1] 중국어로도 요가를 瑜伽라고 하며, 앞 글자의 부수에 영향을 받아 瑜珈라고도 쓴다.

[2] 인더스 문명

[3] 애초에 아리안들이 인도 아대륙에 들어와 원주민들과 격돌하면서 만들어낸 것이 베다 문화인 만큼 차이가 있을 수밖에 없다.

이들은 원주민들을 다사, 다시유라고 부르며 멸시하였다. 이것이 초기 리그베다에서 가장 명확하게 드러나는 카스트의 모습이다.

[4] 요가가 스트레칭 동작이 많아서 그렇지 엄연히 자신의 몸무게를 두팔이나 한 다리만으로 들어올려야 하는 동작도 존재하며,

이런 운동은 아무리 체중 대비 힘이 좋은 사람이라도 일정 수준의 단련 없이는 불가능에 가깝다. 이

렇다보니 무슨 선수급으로 강해지지는 않아도 일반인 수준에서는 상당한 힘과 체력을 얻게되는 것.

[5] 아쉬탕가의 기본이 되는 시퀀스로, 스탠딩 시퀀스를 fundamental이라고 부르기도 한다.

[6] 어드밴스는 다시 A, B, C, D로 구분된다. 다만, C, D는 파바티 조이스가 그의 손자인 샤랏 조이스에게만 전수했다.

때문에 일반적인 수련자들은 B까지 수련이 가능하며, 이 시리즈까지만 대중에 알려져있다.

[7] 실제로 인도 마이솔에 방문하여 파타비 조이스를 직접 만나기도 했었다.

파타비 조이스는 집안에 마돈나의 사진과 싸인을 스승인 크리슈나마차리야의 사진 바로 옆에 전시했다고 알려져있다.

[8] 이 때문에 일본에서는 아쉬탕가를 '헐리우드 파워요가'라고도 부른다.

[9] 마이소르는 아쉬탕가 요가가 시작된 인도의 도시 이름이기도 하며, 여

전히 오늘날에도 전 세계의 아쉬탕가 수련자들은 이곳에 가서 수련을 하고, 수련하는 것을 꿈꾼다.

[10] 물론 한번도 요가를 해보지 않은 생초보들도 마이솔로 아쉬탕가를 시작해도 무방하다.

일부 학원에서는 마이솔로 처음 시작하는 것을 권하기도 한다.

[11] 아쉬탕가에는 파바티 조이스의 '요가 말라'가 있다.

[12] 실제로 걸그룹 프로미스나인의 멤버 송하영이 플라잉 요가 지도사 자격증을 가지고 있다.

[13] #1 #2 영상1 영상2 영상3

[14] 그리고 전세계적으로 요가를 수련하는 상당수는 요가의 신체수련법만을 운동법으로 차용해 배우는게 보통이다.

깊이 파는 사람들은 정신적인 면도 관심을 가지지만...

[15] 요가 하면 보통 인도를 떠올리지만 정작 요가 시장의 중심지는 미국이다.

그럴 수 밖에 없는게 인도인들도 요가를 잘하면서 어찌 이민가자면 미국으로 가서 요가로 돈을 벌고 알리려는 게 많고

사회전반적으로 미국이 시장성도 크고 안정적이라 좋기 때문에 많이 갔고

이들에게 배운 미국인들도 열었기 때문에.

인도는 오히려 강간이나 살인의 위험으로 요가 여행은 그리 가지 않는다. 인도/관광 문서로.

[16] 앞서 나열한 조건들에 다수 해당된다

[17] 오해하는 경우가 있는데 금강영관은 무술이라기보다는 깨달음을 위한 실천적 방편으로 불교수행법의 일종이다.

다만 무술로서의 부분도 가지고 있고 홍보하면서

무술적인 면이 많이 알려졌다.

● yoga 영어단어사전참조

● yoga 관련단어 사전참조

● from 영어 위키 백과https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/yoga

영어 위키 백과 사전참조 [불기 2566-12-29일자 내용 보관 편집 정리]

<구글번역>

요가

무료 백과 사전, 위키피디아에서

내비게이션으로 이동검색으로 이동 운동에 요가를 사용하려면 운동 으로서의 요가를 참조하십시오 .

요가를 요법으로 사용하려면 요법으로서의 요가를 참조하십시오 .

다른 뜻에 대해서는 요가 (동음이의) 문서를 참조하십시오 .

이 문서에는 인도어 텍스트 가 포함되어 있습니다 .

적절한 렌더링 지원 이 없으면 인도어 텍스트 대신

물음표 또는 상자 , 잘못된 모음 또는 누락된 접속사가 표시 될 수 있습니다 .

연꽃 자세 로 명상하는 시바 의 동상

요가 ( / ˈ j oʊ ɡ ə / ( 듣기 )

신체적 , 정신적, 영적 관행 또는 훈련 의 그룹으로

고대 인도 는 마음( 치타 )과

세속적인 고통( 두카 ) 에 의해 손대지 않은

분리된 목격자 의식 을 인식 하여

통제(요크)와 여전히 마음 을 목표로 합니다. ).

힌두교 , 불교 , 자이나교 에는

다양한 종류의 요가, 수행 및 목표 [2] 학교가 있으며 [3] [4] [5]

전통 및 현대 요가는 전 세계적으로 시행되고 있습니다. [6]

요가의 기원에 대한 두 가지 일반적인 이론이 존재합니다

. 선형 모델은 요가가 베다 텍스트 코퍼스 에 반영된 것처럼

베다 시대에 시작되었고 불교에 영향을 미쳤다고 주장합니다.

저자 Edward Fitzpatrick Crangle에 따르면 이 모델은 주로 힌두 학자들이 지지합니다.

합성 모델에 따르면 요가는 비베다 요소와 베다 요소의 합성입니다.

이 모델은 서양 장학금에서 선호됩니다. [7] [8]

요가와 유사한 관행은 Rigveda 에서 처음 언급됩니다 . [9]

요가는 여러 우파니샤드 에서 언급됩니다 . [10] [11] [12]

현대 용어와 같은 의미를 가진 "요가"라는 단어가 처음으로 알려진 것은

기원전 5세기에서 3세기 사이에 작성된 것으로 추정되는

카타 우파니샤드 [13] [14] 에 있습니다. . [15] [16]

요가는

고대 인도의 금욕주의 와

스라마나 운동 에서

기원전 5세기와 6세기 동안

체계적인 연구와 수행으로 계속 발전했습니다 . [17]

요가에 관한 가장 포괄적인 문헌인

Patanjali의 Yoga Sutras는

서력 초기 세기로 거슬러 올라갑니다. [18] [19] [주 1]

요가 철학 은

서기 1000년 후반기에

힌두교 의 6개 정통 철학 학파 ( Darśanas ) 중

하나로 알려지게 되었습니다[20] [웹 1]

하타 요가 텍스트는

9세기에서 11세기 사이에 나타나기 시작했으며

탄트라 에서 유래했습니다 . [21] [22]

서구 세계에서 "요가"라는 용어는

종종 현대적인 형태의 하타 요가와

자세 기반 체력, 스트레스 해소 및 이완 기술을 나타내며 [23]

주로 아사나 로 구성 됩니다.

이것은 명상 과

세속적 인 애착으로부터의 해방 에

초점을 맞추는 전통적인 요가와 다릅니다 . [23] [25]

19세기 말과 20세기 초 에

Swami Vivekananda 의 아사나 없는

요가 적응 이 성공한 후

인도 의 전문가 들 에 의해 소개되었습니다 . [26]

Vivekananda는 Yoga Sutras 를 소개했습니다.

그들은 20세기 하타 요가의 성공 이후 유명해졌습니다. [27]

내용물

1어원

2고전 텍스트의 정의

삼목표

4역사 4.1태생

4.2초기 참조(기원전 1000~500년)

4.3두 번째 도시화(기원전 500~200년)

4.4고전 시대(기원전 200년 – 서기 500년)

4.5중세(서기 500~1500년)

4.6현대 부흥

5전통 5.1자이나교 요가

5.2불교 요가

5.3클래식 요가

5.4아드바이타 베단타

5.5탄트라 요가

5.6하타요가

5.7라야와 쿤달리니 요가

6다른 종교의 수용 6.1기독교

6.2이슬람교

7또한보십시오

8노트

9참조

10출처

11외부 링크

어원

연꽃 자세 로 명상하는 파탄잘리 요가 경전의 저자 파탄잘리의 동상

산스크리트어 명사 요그 요가 는

"부착하다, 연결하다, 묶다, 멍에를 매다"라는

어근 yuj (유즈) 에서 파생되었습니다 .

요가 는 영어 단어 "yoke" 의 동족 입니다 . [29]

Mikel Burley 에 따르면

"요가"라는 단어의 어원이 처음 사용된 것은

Rigveda 의 찬송가 5.81.1 에서 떠오르는 태양신에 대한 헌정에서

"멍에" 또는 ""로 해석되었습니다. 제어". [30] [31] [주 2]

Pāṇini (기원전 4세기)는

요가라는 용어가

유지 르 요가 (멍에를 메다)

또는 유즈 사마다우 ("집중하다") 의

두 어원에서 파생될 수 있다고 썼습니다. [33]

Yoga Sutras 의 맥락 에서

어근 yuj samādhau (집중하다)는

전통적인 주석가들에 의해 올바른 어원으로 간주됩니다. [34]

Pāṇini에 따르면

Vyasa ( 요가 수트라 에 대한 첫 번째 주석을 쓴 사람 ) [35] 는

요가가 삼매 (집중) 를 의미한다고 말합니다 . [36]

Yoga Sutras (2.1)에서

크리야요가는

요가 의 "실용적인" 측면으로,

일상 업무 수행에서 "최고와의 결합"입니다.

요가 를 수련하거나

높은 수준의 헌신으로 요가 철학을 따르는 사람을 요기 라고 합니다 .

여성 요기는 요기니 라고도 합니다 . [38]

고전 텍스트의 정의

요가 라는 용어 는 인도의 철학적, 종교적 전통에서 여러 가지 방식으로 정의되었습니다.

| 소스 텍스트 | 약. 날짜 | 요가의 정의 [39] |

|---|---|---|

| Vaisesika sutra | 씨. 기원전 4세기 | "즐거움과 괴로움은 감각 기관과 마음과 대상이 함께 모여 일어나는 결과입니다. 마음이 자아 안에 있기 때문에 그것이 일어나지 않을 때, 구현된 사람에게는 즐거움과 괴로움이 없습니다. 그것이 요가입니다. " (5.2.15-16) |

카타 우파니샤드 |

기원전 지난 세기 | "오감이 마음과 함께 고요하고 지성이 활동하지 않을 때, 그것이 가장 높은 상태라고 알려져 있습니다. 그들은 요가를 감각의 확고한 억제라고 생각합니다. 그리고 세상을 떠나는 것"(6.10-11) |

바가바드 기타 |

씨. 기원전 2세기 | "성공과 실패에 대해 같은 마음을 가지십시오. 이러한 평정을 요가라고 합니다"(2.48) "요가는 행동하는 기술입니다"(2.50) " 고통과의 접촉에서 분리되는 요가라는 것을 아십시오"(6.23). |

| 파탄잘리의 요가 수트라 | 씨. 1세기 CE [18] [40] [주 1] | 1.2. yogas chitta vritti nirodhah - "요가는 마음의 동요/패턴을 진정시키는

것입니다" 1.3. 그런 다음 Seer 는 자신의 본질적이고 근본적인 본성으로 확립됩니다. 1.4. 다른 상태에서는 (마음의) 수정과 함께 (보는 자의) 동화가 있습니다. |

| Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra (Sravakabhumi) , 대승 불교 Yogacara 작품 | 서기 4세기 | "요가는 믿음, 포부, 인내, 수단의 네 가지입니다"(2.152) |

| Pashupata-sutra 에 Kaundinya의 Pancarthabhasya | 서기 4세기 | "이 시스템에서 요가는 자아와 주님의 결합입니다"(II43) |

| Haribhadra Suri 의 자이나교 작품 Yogaśataka | 서기 6세기 | "확신을 갖고 요긴스의 영주는 우리의 교리에서 요가를 올바른 지식에서 시작되는 세 가지[올바른 지식( sajjñana ), 올바른 교리( saddarsana ) 및 올바른 행위( saccaritra )] 의 동시성( sambandhah )으로 정의했습니다. 발생] 해방과 함께.... 일반적으로 이 [용어] 요가는 결과에 대한 원인의 일반적인 사용으로 인해 이러한 [세]의 원인과 [자아의] 접촉을 나타냅니다." (2, 4). [41] |

| 링가 푸라나 | 서기 7~10세기 | "'요가'라는 단어는 시바 의 상태인 열반을 의미 합니다." (I.8.5a) |

| Brahmasutra -Adi Shankara 의 | 씨. 서기 8세기 | "요가에 관한 논문에서 다음과 같이 말합니다. '요가는 현실을 인식하는 수단입니다'( atha tattvadarsanabhyupāyo yogah )"(2.1.3) |

| Mālinīvijayottara Tantra , 비 이중 카슈미르 Shaivism 의 주요 권위자 중 하나 | 서기 6~10세기 | "요가는 한 개체가 다른 개체와 하나가 되는 것이라고 합니다." (MVUT 4.4–8) [42] |

| Shaiva Siddhanta 학자 Narayanakantha 의 Mrgendratantravrtti | 서기 6~10세기 | "자제력을 갖는 것은 요긴(Yogin)이 되는 것입니다. 요긴(Yogin)이라는 용어는 "반드시 자신의 본성... 시바 상태( sivatvam )와 "결합"하는 사람"을 의미합니다(MrTaVr yp 2a) [42] |

| 락슈마나데시켄드라 의 샤라다틸라카, 샤크타 탄트라 작품 | 서기 11세기 | "요가 전문가들은 요가가 개별 자아(jiva)와 아트만(atman)의 일체성이라고 말합니다. 다른 사람들은 요가가 시바와 자아가 다르지 않음을 확인하는 것이라고 이해합니다. 아가마스의 학자들은 다른 학자들은 그것이 원시 자아에 대한 지식이라고 말합니다." (SaTil 25.1–3b) [43] |

| 하타 요가 요가 비자 | 서기 14세기 | "아파나와 프라나, 자신의 라자와 정액, 태양과 달, 개별 자아와 지고의 자아, 그리고 같은 방식으로 모든 이원성의 결합을 요가라고 합니다."(89) |

목표

요가의 궁극적인 목표는 마음 을 고요하게 하고 통찰력 을 얻고,

분리된 인식에서 쉬고,

윤회 와 duḥkha 로부터의 해방( Moksha ) 입니다.

신성한( Brahman ) 또는 자신 과의 일치( Aikyam )로 이끄는 과정(또는 규율) 입니다. ( 아트만 ). [44]

이 목표는 철학적 또는 신학적 체계에 따라 다릅니다.

고전적인 아스탄가 요가 체계 에서 요가의 궁극적인 목표는

삼매 를 달성 하고 그 상태를 순수한 자각 으로 유지하는 것입니다 .

Knut A. Jacobsen 에 따르면 요가에는 다섯 가지 주요 의미가 있습니다. [45]

목표 달성을 위한 훈련된 방법

몸과 마음을 다스리는 기술

학파 또는 철학 체계의 이름( darśana )

"hatha-, mantra- 및 laya-와 같은 접두사를 사용하여 특정 요가 기술을 전문으로 하는 전통

요가 수련의 목표 [46]

David Gordon White 는 요가의 핵심 원칙이 CE 5세기에 어느 정도 자리를 잡았고

시간이 지남에 따라 다양한 원칙이 발전했다고 썼습니다. [47]

역기능적인 지각과 인지를 발견하고 이를 극복하여 고통을 해소하고 내면의 평화와 구원을 찾는 명상적 수단.

이 원칙의 예는 Bhagavad Gita 및 Yogasutras 와 같은 힌두교 텍스트 ,

여러 불교 Mahāyāna 작품 및 Jain 텍스트에서 찾을 수 있습니다. [48]

자신에서 모든 사람과 모든 것과 공존하는 의식의 고양과 확장.

이것들은 힌두교 베다 문학과 그 서사시인 마하바라타 , 자이나교 프라샤마라티프라카라나, 불교 니카야 텍스트 와 같은 출처에서 논의됩니다 . [49]

무상(환상적, 망상적) 및 영구적(진정한, 초월적) 현실을 이해할 수 있게 해주는

전지전능과 깨달은 의식으로 가는 길.

이것의 예는 불교 Mādhyamaka 텍스트뿐만 아니라

힌두교 Nyaya 및 Vaisesika 학교 텍스트에서 발견되지만 다른 방식입니다. [50]

다른 몸에 들어가 여러 몸을 생성하고 다른 초자연적 성취를 달성하는 기술.

이들은 힌두교와 불교의 탄트라 문헌과 불교 사만나팔라숫타에 기술된 백색 상태입니다.

그러나 제임스 말린슨( James Mallinson ) 은 동의하지 않으며

그러한 비주류 관행은 인도 종교의 해방을 위한 명상 중심의 수단으로서 주류 요가의 목표에서 멀리 떨어져 있다고 제안합니다. [52]

White에 따르면

마지막 원칙은 요가 수련의 전설적인 목표와 관련이 있습니다.

그것은 힌두, 불교, 자이나교 철학 학교에서 공통 시대가 시작된 이래로 남아시아의 생각과 실천에서 요가의 실용적인 목표와 다릅니다. [53]

역사

요가의 연대기나 기원에 대한 합의는

고대 인도에서의 발전 외에는 없습니다.

요가의 기원을 설명하는 두 가지 광범위한 이론이 있습니다.

선형 모델은 요가가 베다의 기원(베다 텍스트에 반영됨)을 가지고 있으며

불교에 영향을 미쳤다고 주장합니다.

이 모델은 주로 힌두교 학자들이 지지합니다.

합성 모델에 따르면 요가는

토착 비베다 관습과 베다 요소를 종합한 것입니다.

이 모델은 서양 장학금에서 선호됩니다. [55]

요가에 대한 추측은

기원전 1000년 전반기 초기 우파니샤드에서 나타나기 시작했으며

설명은 자이나교와 불교 경전에도 나타납니다 .

c. 500 – 다. 기원전 200년 .

기원전 200년에서 기원후 500년 사이에

힌두교, 불교, 자이나교 철학의 전통이 형성되었습니다.

가르침은 경전 으로 수집되었고

Patanjaliyogasastra 의 철학적 체계 가 나타나기 시작했습니다.

중세 시대에는 수많은 요가 위성 전통이 발전했습니다.

그것과 인도 철학의 다른 측면은 19세기 중반에 교육받은 서구 대중의 관심을 끌었습니다.

태생

선형 모델

Edward Fitzpatrick Crangle에 따르면,

힌두 연구자들은 "인도 명상 수행의 기원과 초기 발전을

아리아 기원의 순차적인 성장으로 해석하려는" 선형 이론을 선호했습니다. [57] [주 3]

전통적인 힌두교는 베다 를 모든 영적 지식의 원천으로 간주합니다. [59] [주 4]

Edwin Bryant는 원주민 아리아니즘 을 지지하는 저자들 도

선형 모델을 지지하는 경향이 있다고 썼습니다. [62]

합성 모델

Heinrich Zimmer는 인도의 비베다 동부 국가를 주장하는 합성 모델의 지수였습니다 . [ 63]

짐머에 따르면, 요가는 힌두 철학 , 자이나교 , 불교 의 삼키아 학파 를 포함하는 비베다 체계의 일부 입니다 .

인도 북동부[비하르]의 훨씬 더 오래된 아리안 이전 상류층의 인류학은

요가, 상키아 , 불교, 다른 비베다 인디언 체계와 같은 고대 형이상학적 사색의 하층토에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다." [64] [주 5]

Richard Gombrich [67] 와 Geoffrey Samuel [68] 은 śramaṇa 운동이

비Vedic Greater Magadha 에서 기원 했다고 믿습니다 . [67] [68]

Thomas McEvilley는

Pre-Vedic 기간에 Pre-Aryan 요가 원형이 존재하고

Vedic 기간 동안 개선된 복합 모델을 선호합니다.

Gavin D. Flood에 따르면 우파니샤드는 베다 의식 전통과 근본적으로 다르며

비 베다 영향을 나타냅니다.

그러나 전통은 다음과 같이 연결될 수 있습니다.

그의 이분법은 너무 단순합니다.

왜냐하면 금욕(renunciation)과 베다 브라만교 사이에 연속성이 의심할 여지없이 발견될 수 있는 반면,

브라만교가 아닌 스라마나 전통의 요소도 금욕(renunciation)의 이상적 상태를 형성하는 데 중요한 역할을 했기 때문입니다. [71] [주 6]

동부 갠지스 평원의 금욕적 전통은

프루샤와 프라크리티 라는 공통 분모 의 원삼 키아 개념을 가진

관행과 철학의 공통체에서 나온 것으로 생각됩니다 . [76] [75]

인더스 계곡 문명

20세기 학자인 Karel Werner , Thomas McEvilley 및 Mircea Eliade는 Pashupati 인장 의 중심 인물 이 Mulabandhasana 자세에 있고 [13]

요가의 뿌리가 인더스 계곡 문명 에 있다고 믿습니다 .

이것은 최근의 장학금에 의해 거부되었습니다 .

예를 들어 Geoffrey Samuel , Andrea R. Jain 및 Wendy Doniger 는 식별을 투기적이라고 설명합니다.

그림의 의미는 Harappan 스크립트 가 해독 될 때까지 알 수 없으며

요가의 뿌리는 IVC와 연결될 수 없습니다. [77] [78] [주7]

초기 참조(기원전 1000~500년)

추가 정보: 베다 시대

초기 베다 시대부터 보존되고 c. 기원전 1200년과 900년에는 브라만교 의 변두리나 외부의 고행자와 주로 관련된 요가 수행에 대한 언급이 포함되어 있습니다 .

Rigveda 의 Nasadiya Sukta 는 초기 브라만 명상 전통을 제안 합니다 . [주 8]

호흡과 생명 에너지를 조절하는 기술은 Atharvaveda 와 Brahmanas (Vedas의 두 번째 층, 기원전 1000-800년경에 구성됨)에 언급되어 있습니다. [81] [84] [85]

Flood에 따르면, "The Samhitas [the mantras of the Vedas]에는

금욕주의자, 즉 Munis 또는 Keśins 및 Vratyas에 대한 몇 가지 언급이 포함되어 있습니다."

Werner 는 1977년에 Rigveda 가 요가를 설명하지 않으며 수행에 대한 증거가 거의 없다고 썼습니다. [9]

"브라만 제도에 속하지 않은 외부인"에 대한 최초의 설명은

기원전 1000년경에 성문화된 Rigveda 의 가장 어린 책인 Keśin 찬송가 10.136 에서 찾을 수 있습니다.

Werner 는

... Vedic 신화적 창의성과 Brahminic 종교적 정설의 경향을 벗어나 활동적이어서

그들의 존재, 관행 및 성취에 대한 증거가 거의 없는 개인.

그리고 Vedas 자체에서 사용할 수 있는 그러한 증거는 빈약하고 간접적입니다.

그럼에도 불구하고 간접적인 증거는 영적으로 고도로 진보된 방랑자의 존재에 대해 어떤 의심도 허용하지 않을 만큼 강력합니다. [9]

Whicher (1998)에 따르면, 학문은 종종 리쉬의 명상 수행과 이후의 요가 수행 사이의 연관성을 보지 못합니다 .

여기에는 집중, 명상적 관찰, 수행의 금욕적 형태( 타파스 ), 의식 중 신성한 찬송가 암송과 함께 수행되는 호흡 조절,

자기 희생의 개념, 흠 잡을 데 없이 정확한 신성한 단어 암송( 만트라 요가의 예표 ) 이 포함됩니다. ,

신비로운 경험, 그리고 우리의 심리적 정체성이나 자아보다 훨씬 더 큰 현실과의 관계." [87]

Jacobsen은 2018년에 다음과 같이 썼습니다 . "

희생 을 위한 준비에서" 베다 사제들이 사용하는 금욕적 관행 은 요가의 선구자일 수 있습니다. [81] "

Rgveda 10.136 에 있는 수수께끼 같은 장발 무니 의 황홀한 수행과 브라만교 의식 질서의 외부 또는 주변에 있는 Atharvaveda 에 있는 vratya-s 의 금욕적 수행 은

아마도 요가의 금욕적 수행에 더 많이 기여했을 것입니다." [81]

Bryant에 따르면 고전 요가로 인식할 수 있는 관행은

우파니샤드(후기 베다 시대 에 구성됨 )에 처음 등장합니다.

알렉산더 윈 (Alexander Wynne) 은 형태가 없는 원소 명상이 우파니샤드 전통에서 유래했을 수도 있다는 데 동의합니다.

명상에 대한 초기 언급 은

주요 우파니샤드 중 하나인 브리하다라 냐카 우파니샤드 (기원전 900년경)에서 이루어집니다 .

Chandogya Upanishad ( c. 800-700 BCE)는 다섯 가지 중요한 에너지( prana )를 설명하고

후기 요가 전통(예: 혈관 및 내부 소리)의 개념도 이 upanishad에 설명되어 있습니다. [89]

프라나야마 (호흡에 집중)의 수행 은

브리하다라냐카 우파니샤드의 찬송가 1.5.23 [90] 에 언급되어 있고

프라티야하라 (감각의 철수)는 찬도갸 우파니샤드의 찬송가 8.15에 언급되어 있습니다. [90] [주 9]

Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana (아마 기원전 6세기 이전)는 호흡 조절과 만트라 의 반복을 가르칩니다 . [92]

6세기. BCE Taittiriya Upanishad 는 요가를 몸과 감각의 숙달로 정의합니다.

Flood 에 따르면, " 요가 라는 실제 용어는 Katha Upanishad 에 처음 등장합니다 . [14]

기원전 5 세기 [94] 에서 기원전 1세기로 거슬러 올라갑니다. [95]

두 번째 도시화(기원전 500~200년)

이 부분의 본문 은 두 번째 도시화입니다 .

체계적인 요가 개념은 c로 거슬러 올라가는 텍스트에서 나타나기 시작합니다.

기원전 500~200년, 초기 불교 문헌 ,

중기 우파니샤드, 마하바라타 의 바가바드 기타 와 샨티 파르바 . [96] [주 10]

불교와 스라마나 운동

전사가 아닌 떠돌이 은둔자가 되는 부처 를 묘사한 보로부두르 의 옅은 부조

제프리 사무엘( Geoffrey Samuel ) 에 따르면 ,

"현재까지 가장 좋은 증거"는

요가 수련이 " 아마도 기원전 6세기와 5세기경에

초기 스라마나 운동( 불교 , 자이나교 , 아지비카 )과 같은

금욕계에서 발전했다"는 것을 시사합니다 .

이것은 인도의 두 번째 도시화 기간 동안 발생했습니다. [17]

Mallinson과 Singleton에 따르면, 이러한 전통은

심신 기술( Dhyāna 및 타파스 로 알려짐 )을 처음으로 사용했지만

나중에는 재생의 순환에서 해방을 위해 노력하는 요가로 설명되었습니다. [99]

Werner는 "부처님은 자신의 [요가] 시스템의 창시자였습니다.

인정하건대, 그는 이전에 여러 요가 교사 밑에서 얻은 경험 중 일부를 활용했습니다." [100]

그는 다음과 같이 언급합니다. [101]

그러나 체계적이고 종합적이거나 통합적인 요가 수행 학교에 대해 말할 수 있는 것은

팔리어 정경에 설명된 대로 불교 자체에 대해서만 가능 합니다. [101]

초기 불교 경전은 요가와 명상 수련에 대해 설명하고 있으며,

그 중 일부는 붓다가 스라마나 전통에서 차용한 것입니다. [102] [103]

팔리어 경전 ( Pāli Canon )에는 부처님이 구절에 따라 배고픔이나 마음을 조절하기 위해

혀를 입천장에 대고 누르는 것을 묘사하는 세 구절이 포함되어 있습니다.

khecarī mudrā 에서와 같이 비인두 에 삽입된 혀에 대한 언급은 없습니다 .

붓다는 쿤달리니 를 불러일으키는 현대의 자세와 유사하게 발뒤꿈치로 회음부 에 압력을 가하는 자세를 사용했다 . [105]

요가 수행을 논의하는 경은 다음을 포함합니다.

Satipatthana Sutta ( 마음챙김 경의 네 가지 기초 Sutta ) 및 Anapanasati Sutta( 호흡 의 마음챙김 Sutta ).

고대 힌두 경전처럼 요가와 관련된 초기 불교 경전의 연대기는 불분명합니다.

Majjhima Nikāya 와 같은 초기 불교 자료에서는 명상 을 언급합니다.

Aṅguttara Nikāya 는 muni , Kesin 및 명상 수행자에 대한 초기 힌두교 설명과 유사한 jhāyins(명상가)를 설명 하지만 [ 108]

이 텍스트에서는 명상 수행을 "요가"라고 부르지 않습니다.

현대적 맥락에서 이해되는 불교 문학에서 요가에 대한 가장 초기의 알려진 논의는

후기 불교 요가카라 와 상좌부 학파에서 나온 것입니다. [109]

자이나교 명상 은 불교 학교 이전의 요가 시스템입니다.

그러나 자이나교 자료는 불교 자료보다 후기이기 때문에

초기 자이나파와 다른 유파에서 파생된 요소를 구분하기 어렵다.

우파니샤드 와 일부 불교 경전에서 언급된 대부분의 다른 현대 요가 체계는 소실되었습니다. [111] [112] [주11]

우파니샤드

후기 베다 시대 에 작곡된 우파니샤드 는 고전 요가로 인식할 수 있는 수련에 대한 최초의 언급을 담고 있습니다. [73]

현대적 의미에서 "요가"라는 단어가 처음으로 알려진 것은 카타 우파니샤드 [13] [14]

(아마도 기원전 5세기에서 3세기 사이에 구성됨) [ 15] [16]

정신 활동의 중단과 함께 최고의 상태로 이끄는 감각의 꾸준한 통제로서. [86] [주 12]

카타 우파니샤드 는 초기 우파니샤드 의 일원론 을 상 키아 와 요가의 개념과 통합합니다.

그것은 자신과의 근접성에 따라 존재 수준을 정의합니다.

내면의 존재 .

요가는 내면화 과정 또는 의식 상승 과정으로 간주됩니다. [115] [116]

우파니샤드는 요가의 기본을 강조하는 최초의 문학 작품입니다. 화이트에 따르면,

요가에 대한 현존하는 최초의 체계적 설명과 초기 베다 용어 사용의 다리는 기원전 3세기경으로 거슬러 올라가는 힌두교 경전인

카타 우파니샤드(Ku)에서 발견됩니다.

마음의 계층 구조를 설명합니다.

-신체 구성 요소 - 감각, 마음, 지성 등 - Sāmkhya 철학의 기본 범주를 구성하는 형이상학적 체계는

Yogasutras, Bhagavad Gita 및 기타 텍스트 및 학교의 요가를 기반으로 합니다(Ku3.10–11; 6.7– 8). [117]

Shvetashvatara Upanishad 2권의 찬송가 (기원전 1000년 후반의 또 다른 텍스트)는

몸을 똑바로 세우고 호흡을 억제하며 마음을 명상적으로 집중하는 절차를 설명합니다.

그리고 조용합니다. [118] [119] [116]

Maitrayaniya Upanishad 는 아마도 Katha 및 Shvetashvatara Upanishads보다 나중에 작성되었지만

Patanjali의 Yoga Sutras 이전 에 6 중 요가 방법 을 언급합니다 . 노조 . [13] [116] [120]

교장 우파니샤드에서의 토론 외에도 20개의 요가 우파니샤드 및 관련 텍스트(예: CE 6세기에서 14세기 사이에 작성된

Yoga Vasistha )에서 요가 방법에 대해 논의합니다. [11] [12]

마케도니아어 텍스트

알렉산더 대왕 은 기원전 4세기에 인도에 도달했습니다. 그의 군대 외에도 그는 지리, 민족 및 관습에 대한 회고록을 쓴 그리스 학자들을 데려 왔습니다. Alexander의 동료 중 한 명은 요기를 설명하는 Onesicritus ( Strabo 가 그의 지리학 에서 Book 15, Sections 63–65에서 인용 )였습니다. [121] Onesicritus는 수행자들이 냉담했고 "다른 자세 – 서 있거나 앉거나 알몸으로 누워 – 움직이지 않는" 자세를 취했다고 말합니다. [122]

Onesicritus는 또한 동료 Calanus 가 그들을 만나려는 시도를 언급합니다. 처음에는 청중을 거부했지만 나중에 "지혜와 철학에 호기심이 많은 왕"이 보냈기 때문에 초대되었습니다. [122] Onesicritus와 Calanus는 요가 수행자들이 "고통뿐 아니라 즐거움도 제거하는 정신", "인간은 그의 의견이 강화될 수 있도록 수고를 위해 몸을 훈련한다"는 삶의 최고의 교리를 고려한다는 것을 배웁니다. 검소한 요금으로 사는 것은 부끄러운 일이 아닙니다." 그리고 "살기 가장 좋은 곳은 장비나 옷이 가장 부족한 곳입니다. [121] [122] Charles Rockwell Lanman 에 따르면, 이러한 원칙은 요가의 영적 측면의 역사에서 중요하며 Patanjali 와 Buddhaghosa 의 후기 작품에서 "평온한 평온"과 "균형을 통한 마음 챙김"의 뿌리를 반영할 수 있습니다 . [121]

마하바라타 와 바가바드 기타

요가의 초기 형태인 니로다요 가(종료의 요가)는 기원전 3세기 마하바라타 12장( 샨티 파르바 )의 모크샤달마 섹션에 설명되어 있습니다. Nirodhayoga 는 푸루샤 (자아)가 실현 될 때까지 생각과 감각을 포함한 경험적 의식에서 점진적인 철수를 강조 합니다 . Patanjali의 용어 와 유사한 vichara (미묘한 반성) 및 viveka (차별)와 같은 용어가 사용되지만 설명하지는 않습니다. 마하바라타 에는 획일적인 요가 목표가 포함되어 있지 않지만, 물질로부터 자아를 분리하고 브라만 에 대한 인식을 모든 곳은 요가의 목표로 묘사됩니다. Samkhya 와 요가는 융합 되어 있으며 일부 구절에서는 동일하다고 설명합니다. Mokshadharma 는 또한 원소 명상의 초기 수행을 설명합니다. 마하바라타 는 요가의 목적을 모든 것에 스며드는 보편적인 브라만과 개별 아트만을 통합하는 것으로 정의 합니다 . [125]

아르주나 에게 바가바드 기타 를 설명하는 크리슈나

Mahabharata 의 일부인 Bhagavad Gita ( 주님의 노래 ) 에는 요가에 대한 광범위한 가르침이 포함되어 있습니다.

Mallinson과 Singleton에 따르면, Gita 는 "자신의 카스트와 삶의 단계에 따라 수행되는 세속적 활동과 양립할 수 있다고 가르치면서

요가가 시작된 포기한 환경에서 적합한 요가를 추구합니다. 포기한다." [123]

전통적인 요가 수련(명상 포함)에 전념하는 장(6장) 외에도 [127]

요가의 세 가지 중요한 유형을 소개합니다. [128]

카르마 요가 : 행동의 요가 [129]

박티 요가 : 헌신의 요가 [129항]

즈나나 요가 : 지식의 요가 [130] [131]

기타 는 18개의 장과 700개의 시로 구성되어 있습니다 .

각 장은 다른 형태의 요가 이름을 따서 명명되었습니다. [132] [133] [134]

일부 학자들은 기타 를 세 부분으로 나눕니다.

처음 6장(280 shlokas )은 카르마 요가, 중간 6장(209 shlokas )은 박티 요가,

마지막 6장(211 shlokas 는 jnana 요가)을 다루고 있습니다.

그러나 세 가지 요소 모두 작업 전반에 걸쳐 발견됩니다. [132]

철학 경전

요가는 힌두 철학의 기본 경전 에서 논의 됩니다 .

기원전 6세기에서 2세기 사이에 작성된

힌두교 의 Vaisheshika 학교 의 Vaiśeṣika Sūtra 는 요가에 대해 논의합니다. [주 13]

Johannes Bronkhorst 에 따르면 Vaiśeṣika Sūtra 는 요가를

"마음이 자아에만 있고 따라서 감각에 있지 않은 상태"라고 설명합니다.

이것은 pratyahara (감각의 철회) 와 동일 합니다.

경전은 요가가 수카 (행복)와 둑카 의 부재로 이어진다고 주장합니다

.(고통), 영적 해방을 향한 여정의 명상 단계를 설명합니다. [135]

힌두교 베단타 학파 의 기본 텍스트인 브라흐마 수트라 ( Brahma Sutras ) 에서도 요가에 대해 논의합니다. [136]

기원전 450년에서 기원후 200년 사이에 살아남은 형태로 완성된 것으로 추정되는 [137] [138] 그 경전은

요가가 "신체의 미묘함"을 얻는 수단이라고 주장합니다.

Nyaya Sutras — BCE 6세기와 CE 2세기 사이에 구성된 것으로 추정되는 Nyaya 학교 의 기초 텍스트 [ 139 ] [140]

— 경전 4.2.38–50에서 요가에 대해 논의합니다.

요가 윤리, 디야 나(명상) 및 삼매 에 대한 토론이 포함됩니다.,

토론과 철학도 요가의 한 형태라는 점에 주목합니다. [141] [142] [143]

고전 시대(기원전 200년 – 서기 500년)

힌두교, 불교, 자이나교의 인도 전통은 마우리아 시대 와 굽타 시대(기원전 200년경~서기 500년경) 사이에 형성되었고

요가 체계가 등장하기 시작했습니다.

이러한 전통 의 여러 텍스트에서 요가 방법과 관행에 대해 논의하고 편집했습니다.

그 시대의 주요 작품으로는 Patañjali의 Yoga Sūtras ,

Yoga -Yājñavalkya ,

Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra 및 Visuddhimagga 가 있습니다.

파탄잘리의 요가 수트라

파탄잘리 를 신성한 뱀 셰샤 의 화신으로 묘사한 전통적인 힌두교의 묘사

브라만 요가 사상 의 가장 잘 알려진 초기 표현 중 하나는

Patanjali의 Yoga Sutras

(초기 CE, [18] [40] [주 1] 원래 이름은 Pātañjalayogaśāstra-sāṃkhya-pravacana (c. 325–425 CE); 일부 학자들은 경전과 주석이 포함되어 있다고 믿습니다. [144]

이름에서 알 수 있듯이 텍스트의 형이상학적 기반은 samkhya입니다 .

이 학교는 Kautilya의 Arthashastra 에서 anviksikis 의 세 가지 범주 중 하나로 언급됩니다.

(철학), 요가와 Cārvāka . [145] [146]요가와 상캬는 약간의 차이가 있습니다.

요가는 인격신의 개념을 받아들였고,

삼키야는 힌두 철학의 이성적이고 무신론적인 체계였다. [147] [148] [149]

Patanjali의 시스템은 때때로 "Seshvara Samkhya"라고 불리며 Kapila 의 Nirivara Samkhya 와 구별됩니다 . [150]

요가와 삼키야 사이의 유사점은

막스 뮐러( Max Müller )가 말하기를

"두 철학은 대중적 용어로 서로 구별되는 삼키아(Samkhya with Lord)와 삼키야(Samkhya with a Lord)"라고 말할 정도로 유사합니다.

Karel Werner 는 중기 및 초기 Yoga Upanishads에서 시작된 요가의 체계화가

Patanjali의 Yoga Sutras 에서 절정에 이르렀다고 썼습니다 .[주 14]

| 파탄잘리의 요가 경전 [153] | ||

|---|---|---|

| 파다(장) | 영어 의미 | 경전 |

| 사마디 파다 | 영혼에 흡수되어 | 51 |

| 사다나 파다 | 영에 잠긴 것에 대하여 | 55 |

| 비부티 파다 | 초자연적인 능력과 은사에 대하여 | 56 |

| 카이발야 파다 | 절대적인 자유에 대하여 | 34 |

요가 수트라 는

또한 불교와 자이나교의 스라마나 전통의 영향을 받았으며

이러한 전통에서 요가를 채택하려는 브라만교적 시도일 수 있습니다.

라슨 은 특히 기원전 2세기부터 서기 1세기까지

고대 삼키야, 요가, 아비달마 불교 의 여러 유사점에 주목했습니다 .

Patanjali 의 Yoga Sutras 는 세 가지 전통의 종합입니다.

Samkhya에서 그들은 prakrti 와 purusa (이원론) 의 "반성적 식별"( adhyavasaya ) , 그들의 형이상학적 합리주의, 지식을 얻는 세 가지 인식론적 방법을 채택합니다. [154

]Larson은 Yoga Sutras 가 Abhidharma 불교의 nirodhasamadhi 에서 변경된 인식 상태를 추구한다고 말합니다 .

그러나 불교의 "무자아 또는 영혼"과는 달리 요가(삼키야와 같은)는 각 개인이 자아를 가지고 있다고 믿습니다.

요가 수트라 가 종합 하는 세 번째 개념 은 명상과 성찰 의 금욕적 전통이다. [154]

Patanjali의 Yoga Sutras 는 요가 철학의 첫 번째 모음집으로 간주됩니다. [주 15]

요가 수트라 의 구절 은 간결합니다.

후기의 많은 인도 학자들이 그것들을 연구하고

Vyasa Bhashya (c. 350–450 CE) 와 같은 주석을 출판했습니다 .

Patanjali 는 그의 두 번째 경전에서 "요가"라는 단어를 정의하고

그의 간결한 정의는 세 가지 산스크리트어 용어의 의미에 달려 있습니다.

IK Taimni 는 그것을 "요가는 마음( citta ) 의 변형( vṛtti )의 억제( nirodhaḥ )"라고 번역합니다 . [156]

스와미 비베카난다 경을

"요가는 다양한 형태( Vrittis ) 를 취하지 못하도록 마음의 물건( Citta )을 억제하고 있습니다."라고 번역합니다. [157]

에드윈 브라이언트 는 파탄잘리에게 "요가는 본질적으로 능동적이거나 담론적인 사고의 모든 방식으로부터 자유로운 의식 상태에 도달하고

궁극적으로 의식이 자신 외부의 어떤 대상도 인식하지 못하는 상태에 도달하는 명상 수련으로 구성됩니다.

즉, 다른 대상과 혼합되지 않은 의식으로서 자신의 본성을 인식할 뿐입니다." [158] [159] [160]

Baba Hari Dass 는 요가가 nirodha (정신적 통제) 로 이해된다면 요가 의 목표는

"무조건의 niruddha (그 과정의 완성) 상태"라고 썼습니다. [161]

"요가(결합)는 이중성을 의미합니다(두 가지 또는 원리의 결합에서와 같이).

요가의 결과는 하위 자아와 상위 자아의 결합으로서의 비이원적 상태입니다.

비이원적 상태는 다음과 같은 특징이 있습니다. 개성의 부재;

그것은 영원한 평화, 순수한 사랑, 자아 실현 또는 해방으로 묘사될 수 있습니다." [161]

Patanjali 는 Yoga Sutras 2.29 에서 팔다리 요가 를 정의했습니다.

Yama (다섯 가지 금욕):

Ahimsa (비폭력, 다른 생명체에 해를 끼치지 않음), [162]

Satya (진실함, 거짓 없음), [163]

Asteya (도둑질 금지), [164]

Brahmacharya (독신, 자신의 파트너에 대한 충성), [164] 및

Aparigraha (비탐욕, 비소유). [163]

Niyama (다섯 가지 준수):

Śauca (순결, 정신, 언어 및 신체의 명료함), [165]

Santosha (만족, 타인과 자신의 상황 수용), [166]

Tapas (지속적인 명상, 인내, 금욕) , [167]

Svādhyāya (자기 연구, 자기 성찰, Vedas 연구), [168] 및

Ishvara-Pranidhana (신/최고 존재/진정한 자아에 대한 묵상). [166]

Asana : 문자 그대로 "좌석"을 의미하며 Patanjali의 Sutras에서는 명상에 사용되는 앉은 자세를 나타냅니다.

Pranayama ("호흡 운동"): Prāna , 호흡, "āyāma", "스트레칭, 확장, 제지, 중지".

Pratyahara ("추상화"): 외부 물체로부터 감각 기관을 철수하는 것.

Dharana ("집중"): 단일 대상에 주의를 고정합니다.

디야나 ("명상"): 명상 대상의 본질에 대한 강렬한 숙고.

Samadhi ("해방"): 명상의 대상과 의식을 합치는 것.

12세기 이후 힌두 스콜라주의에서

요가는 베다를 받아들이는 전통인 6개의 정통 철학 학파(darsanas) 중 하나였습니다. [주 16] [주 17] [169]

요가와 베단타

요가와 베단타 는 힌두 전통에서 살아남은 가장 큰 두 학교입니다.

그들은 많은 원칙, 개념 및 자아에 대한 믿음을 공유하지만 정도, 스타일 및 방법이 다릅니다.

요가는 지식을 얻는 세 가지 방법을 받아들이고 Advaita Vedanta 는 받아들입니다.

요가는 Advaita Vedanta의 일원론 에 대해 이의를 제기 합니다.

목샤 의 상태에서 각 개인은 행복하고 해방된 자신의 감각을 독립적인 정체성으로 발견 한다고 믿습니다.

Advaita Vedanta는 moksha 의 상태에서, 각 개인은 모든 것, 모든 사람 및 보편적 자아와 하나됨의 일부로서 행복하고 해방되는 자신의 감각을 발견합니다.

그들은 둘 다 자유로운 양심이 초월적이고 해방적이며 자각적이라고 주장합니다.

Advaita Vedanta는 또한 최고의 선과 궁극적인 자유 를 추구하는 사람들을 위해 Patanjali의 요가 수련과 Upanishads 의 사용을 권장합니다 . [171]

요가 야즈나발캬

이 부분의 본문 은 요가 야즈나발캬입니다 .

Syogo Yog 이튜크토 지바트마뜨마노쓰

saṁyogo 요가 ityukto jīvātma-paramātmanoḥ॥

요가는 개별 자아( jivātma )와 지고의 자아( paramātma )의 결합입니다.

— 요가 야즈나발캬 [172]

Yoga Yajnavalkya는 Yajnavalkya 와 유명한 철학자 Gargi Vachaknavi 사이의 대화 형식으로 Vedic 현자 Yajnavalkya 에 기인 한 요가에 대한 고전적인 논문입니다 .

12장 본문 의 기원은 기원전 2세기와 기원후 4세기로 거슬러 올라갑니다.

Hatha Yoga Pradipika , Yoga Kundalini 및 Yoga Tattva Upanishads 와 같은 많은 요가 텍스트는 Yoga Yajnavalkya 에서 차용했습니다(또는 자주 참조) .

여덟 가지 요가 아사나에 대해 논의 합니다 .(Swastika, Gomukha, Padma, Vira, Simha, Bhadra, Mukta 및 Mayura),

신체 정화, [177] 및 명상 을 위한 수많은 호흡 운동 . [178]

아비달마와 요가차라

4세기 학자이자 대승불교의 Yogachara("요가 수련") 학파의 공동 설립자인 Asanga [179]

Abhidharma 의 불교 전통은

Mahayana 및 Theravada 불교 에 영향을 준 불교 이론 및 요가 기술에 대한 가르침을 확장한 논문을 낳았 습니다.

굽타 시대 (서기 4~5세기) 절정기에 요가카라 로 알려진 북부 대승 운동 이

불교 학자 아산가와 바수반두의 저서로 체계화 되기 시작 했습니다 .

Yogācāra 불교는 깨달음과 완전한 성불 을 향해 보살 을 인도하는 실천을 위한 체계적인 틀을 제공했습니다 . [180]

그 가르침은 백과사전 인 Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra 에서 찾을 수 있습니다.( 요가 수련자를 위한 논문 )은 티베트어와 중국어로도 번역되어

동아시아 와 티베트 불교 전통에 영향을 미쳤습니다.

Mallinson 과 Singleton은 요가의 초기 역사를 이해하는 데 요가카라 불교 연구가 필수적이며

요가의 가르침이 Pātañjalayogaśāstra에 영향을 미쳤다고 썼습니다.

남인도와 스리랑카에 기반을 둔 Theravada 학교는

또한 주로 Vimuttimagga와 Visuddhimagga와 같은 요가 및 명상 훈련을 위한 매뉴얼 을 개발 했습니다 .

자이나교

상위 문서: 자이나교

2세기에서 5세기 자이나교 문헌인 Tattvarthasutra 에 따르면

요가는 마음, 말, 몸의 모든 활동의 합입니다.

Umasvati 는 요가를 카르마 의 생성자라고 부르며 [ 183] 해방의 길에 필수적입니다.

그의 Niyamasara 에서 Kundakunda 는 요가 박티 (해방의 길에 대한 헌신)를 가장 높은 형태의 헌신으로 묘사 합니다.

Haribhadra 와 Hemacandra 는 요가에서 고행자의 다섯 가지 주요 서약과 평신도의 12가지 작은 서약에 주목합니다 .

로버트 J. 자이덴보스 에 따르면 , Jainism은 종교가 된 요가 사상 체계입니다. [185]

파탄잘리 요가 수트라의 다섯 가지 야마 (제약)는

자이나교의 다섯 가지 주요 서약 과 유사하며

이러한 전통 사이의 교차 수정을 나타냅니다. [185] [주 18]

자이나교 요가에 대한 힌두교의 영향 은

파탄잘리의 8중 요가에 영향을 받은 8중 요가를 설명하는

하리바드라의 Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya 에서 볼 수 있습니다. [187]

중세(서기 500~1500년)

_LACMA_M.2011.156.4_(1_of_2).jpg/168px-Female_Ascetics_(Yoginis)_LACMA_M.2011.156.4_(1_of_2).jpg)

17세기와 18세기 인도의 남녀 요기

중세 시대에는 위성 요가 전통이 발전했습니다.

이 시기에 하타 요가 가 등장했습니다. [188]

박티 운동

상위 문서: 박티 요가

중세 힌두교에서 박티 운동 은 인격신 또는 최고 인격 의 개념을 옹호했습니다 .

6~9세기에 남인도 의 알바르족 에 의해 시작된 운동 은 12~15세기에 인도 전역에 영향을 미쳤다.

Shaiva 및 Vaishnava bhakti 전통은 Yoga Sutras (예: 명상 운동)의 측면을 헌신과 통합 했습니다.

Bhagavata Purana 는 크리슈나에 대한 집중을 강조하는 viraha (분리) bhakti 로 알려진 요가의 한 형태를 설명합니다 . [191]

탄트라

탄트라 는 5세기 CE에 의해 인도에서 발생하기 시작한 밀교 전통의 범위입니다. [192] [주 19]

그것의 사용은 Rigveda 에서 tantra 라는 단어가 "기술"을 의미한다는 것을 암시합니다.

조지 새뮤얼은 탄트라 가 논쟁의 여지가 있는 용어라고 썼지만,

10세기경에 불교와 힌두 경전에서 거의 완전한 형태로 탄트라 관습이 나타난 학파로 간주될 수 있습니다.

탄트라 요가는 우주의 축소판으로서 신체에 대한 명상을 포함하는 복잡한 시각화를 개발했습니다.

그것은 진언, 호흡 조절, 신체 조작( 나디 와 차크라 포함)을 포함했습니다..

차크라와 쿤달리니에 대한 가르침은 이후 형태의 인도 요가의 중심이 되었습니다. [195]

탄트라 개념은 힌두교, 본 , 불교, 자이나교 전통에 영향을 미쳤습니다.

탄트라 의식의 요소는 동아시아 와 동남아시아 의 중세 불교 및 힌두 왕국의 국가 기능에 의해 채택되고 영향을 받았습니다 .

1천년이 되자 하타 요가 는 탄트라 에서 나왔다 . [21] [197]

금강승과 티베트불교

Vajrayana 는 Tantric Buddhist 및 Tantrayāna 로도 알려져 있습니다.

그 텍스트는 CE 7세기에 편찬되기 시작했고

티베트어 번역은 다음 세기에 완성되었습니다.

이 탄트라 경전은 티벳으로 수입된 불교 지식의 주요 원천이었으며 [198]

나중에 중국어와 다른 아시아 언어로 번역되었습니다.

불교 문헌 Hevajra Tantra 와 caryāgiti 는 차크라의 계층을 소개했습니다.

요가는 탄트라 불교에서 중요한 수련이다 . [200] [201] [202]

탄트라 요가 연습에는 자세와 호흡 운동이 포함됩니다.

Nyingma 학교 는 호흡 운동, 명상 및 기타 운동을 포함하는 훈련인 얀트라 요가 를 시행합니다.

닝마 명상은 크리야 요가 , 우파 요가, 요가 야나, 마하 요가 , 아누 요가 , 아티 요가와 같은 [204] 단계 로 나뉩니다 .

Sarma 전통에는 Kriya, Upa("Charya"라고 함) 및 요가가 포함되며,

mahayoga 와 atiyoga를 대체 하는 anuttara 요가 가 있습니다. [206]

선도

그의 이름 이 중국 찬을 통해 산스크리트 디야 나 에서 파생된 젠 [주 20] 은

요가가 필수적인 부분인 대승불교의 한 형태입니다. [208]

중세 하타 요가

11세기 Nath 전통 요기이자 하타 요가의 지지자 인 Gorakshanath 의 조각 [209]

하타 요가에 대한 최초의 언급은 8세기 불교 작품에서 찾아볼 수 있습니다.

하타 요가의 가장 초기 정의는 11세기 불교 경전 Vimalaprabha 에 있습니다.

Hatha 요가는 Patanjali의 Yoga Sutras 의 요소 를 자세 및 호흡 운동과 혼합합니다.

그것은 현재 대중적으로 사용되는 전신 자세로의 아사나의 발전을 나타내며

현대 적인 변형과 함께 현재 "요가"라는 단어와 관련된 스타일입니다. [213]

시크교

요가 그룹은 시크교 가 시작된 15세기와 16세기 에 펀자브 에서 두각을 나타냈습니다.

구루 나나크 (시크교 창시자)의 작품은 그가 요가를 수련하는 힌두교 공동체인 요기스(Jogis)와 나눈 대화를 묘사 합니다 .

Guru Nanak은 하타 요가와 관련된 금욕, 의식 및 의식을 거부하고

대신 사하자 요가 또는 나마 요가를 옹호했습니다.

Guru Granth Sahib 에 따르면 ,

오 요기, 나낙은 진실 외에는 아무 말도 하지 않습니다.

마음을 다스려야 합니다.

헌애자는 신성한 말씀을 묵상해야 합니다.

연합을 가져오는 것은 그분의 은혜입니다.

그는 이해하고 또한 본다. 선행은 사람이 운세에 합쳐지는 데 도움이 됩니다. [215]

현대 부흥

서양에서의 소개

1896년 런던의 스와미 비베카난다

요가와 인도 철학의 다른 측면은 19세기 중반에 교육받은 서구 대중의 관심을 끌게 되었고

NC Paul 은 1851 년 에 요가 철학에 관한 논문을 발표했습니다 .

1890년대에 유럽과 미국을 순회하며 서양 청중에게 요가를 소개했습니다.

그의 환영은 뉴잉글랜드 초월주의자 를 포함하는 지식인들의 관심을 바탕으로 이루어졌습니다 .

그들 중에는 게오르그 빌헬름 프리드리히 헤겔( Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel )과 같은 독일 낭만주의 와 철학자 및 학자 를

그린 랄프 왈도 에머슨 (Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1803–1882)이 있었습니다. (1770–1831),

아우구스트 빌헬름 슐레겔 (1767–1845),

프리드리히 슐레겔 (1772–1829), 막스 뮐러 (1823–1900),

아르투르 쇼펜하우어 (1788–1860) 형제. [218] [219]

헬레나 블라바츠키 를 포함한 신지 학자 들도 요가에 대한 서양 대중의 견해에 영향을 미쳤다.

19세기 말 밀교적 견해는 베단타와 요가의 수용을 장려했으며,

영적 세계와 육체적 세계 사이의 일치를 보여주었습니다 .

요가와 베단타 의 수용은 19세기와 20세기 초 동안 (주로 신플라톤 주의적) 종교적, 철학적 개혁과 변혁 의 흐름 과 얽혀 있었습니다.

Mircea Eliade 는 Yoga: Immortality and Freedom 에서 탄트라 요가를 강조하면서

요가에 새로운 요소를 도입 했습니다 . [222]

탄트라 전통과 철학이 도입되면서 요가 수련에 의해 달성된 "초월"의 개념이 마음에서 몸으로 옮겨갔습니다. [223]

운동으로서의 요가

이 부분의 본문 은 운동으로서의 요가입니다 .

서구 세계의 자세 요가는 아사나로 구성된 신체 활동입니다(종종 부드러운 전환 으로 연결되며 때로는 호흡 운동을 동반하고

일반적으로 휴식 또는 명상 기간으로 끝납니다.

종종 단순히 "요가"로 알려져 있습니다. [224]

아사나가 거의 또는 전혀 역할을 하지 않는 더 오래된 힌두 전통(일부는 요가 수트라 로 거슬러 올라감 )에도 불구하고,

아사나는 어떤 전통의 중심도 아니었습니다. [225]

운동으로서의 요가는 Shri Yogendra 와 Swami Kuvalayananda 가 개척한 서양 체조와 하타 요가의 20세기 혼합인 현대 요가 르네상스의 일부입니다 .

1900 년 이전에 하타 요가는 서 있는 자세가 거의 없었다.

Sun Salutation 은 1920년대에 Aundh의 Rajah인 Bhawanrao Shrinivasrao Pant Pratinidhi에 의해 개척되었습니다.

체조 에서 사용되는 많은 서 있는 자세 는 1930년대와 1950년대 사이 마이소르의 Krishnamacharya 에 의해 요가에 통합되었습니다 .

그의 학생들 중 몇몇은 요가 학교를 설립했습니다.

Pattabhi Jois 는 ashtanga vinyasa 요가 를 만들었습니다 . [230]

파워 요가 로 이어졌습니다 .

BKS Iyengar 는 1966년 그의 저서 Light on Yoga 에서 Iyengar Yoga 를 만들고 아사나를 체계화했습니다 .

Indra Devi 는 할리우드 배우들에게 요가를 가르쳤습니다.

Krishnamacharya의 아들 TKV Desikachar 는 첸나이 에서 Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandalam을 설립했습니다 .

20세기에 설립된 다른 학교로는 Bikram Choudhury 의 Bikram Yoga 와 Rishikesh 의 Sivananda 요가 의 Swami Sivananda 가 있습니다 .

. 현대 요가는 전 세계에 퍼졌습니다. [236] [237]

.jpg/220px-thumbnail.jpg)

2016년 뉴델리 국제 요가의 날

요가에 사용되는 아사나의 수는

1830년의 84개( Joga Pradipika 에 설명된 대로 )에서 Light on Yoga 의 약 200개,

1984년에는 Dharma Mittra 가 수행한 900개 이상 으로 증가했습니다.

하타 요가(에너지를 통한 영적 해방)의 목표는 대체로 피트니스 및 휴식의 목표로 대체되었으며

더 난해한 구성 요소 중 많은 부분이 축소되거나 제거되었습니다. "

하타 요가"라는 용어는 종종 여성 을 위한 부드러운 요가를 의미하기도 합니다 . [239]

요가는 수업, 교사 인증, 의복, 책, 비디오, 장비 및 휴일을 포함하는 전 세계적으로 수십억 달러 규모의 비즈니스로 발전했습니다.

고대의 다리를 꼬고 있는 연꽃 자세 와 싯다사나 는 널리 알려진 요가의 상징입니다. [241]

유엔 총회 는 6월 21일을 국제 요가의 날로 지정 했으며 [242] [243] [244]

2015년부터 매년 전 세계에서 기념하고 있습니다. [245] [246]

2016년 12월 1일, 요가는 유네스코 에 의해 무형문화유산 으로 등재되었습니다 . [247]

자세 요가가 신체 및 정신 건강에 미치는 영향은 연구 대상이 되어 왔으며

규칙적인 요가 수련이 요통과 스트레스에 유익하다는 증거가 있습니다. [248] [249]

2017년 Cochrane 리뷰에서는 만성 요통 을 위해 고안된 요가 개입 이 6개월 표시에서 기능을 증가시키고

3-4개월 후에 통증을 완만하게 감소시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.

통증의 감소는 요통을 위해 고안된 다른 운동 프로그램과 유사한 것으로 나타났지만,

그 감소는 임상적으로 유의미한 것으로 간주될 만큼 크지는 않았습니다.

이러한 변화의 기초가 되는 메커니즘 이론에는

근력과 유연성의 증가, 육체적 정신적 이완, 신체 인식의 증가가 포함됩니다 .

전통

요가는 모든 인도 종교 에서 다양한 방법으로 수행됩니다 .

힌두교에서는 jnana 요가 , bhakti 요가 , karma 요가 , kundalini 요가 및 hatha 요가 가 수행 됩니다.

자이나교 요가

상위 문서: 자이나교 명상

요가는 자이나교 의 중심 수행이었습니다 .

자이나교 영성은

엄격한 비폭력 규범,

즉 아힘사 ( 채식주의 포함 ), 자선( 다나 ), 세 가지 보석 에 대한 믿음, 금식 과 같은 긴축( 타파스 ) , 요가를 기반으로 합니다. [251] [252]

자이나교 요가는 자아를 환생 의 순환에 묶는 카르마 의 세력으로부터 자아를 해방하고 정화하는 것을 목표로 합니다 .

요가와 상키아처럼 자이나교는 각자의 카르마에 묶인 여러 개인을 믿습니다. [253]

카르마의 영향을 줄이고 축적된 카르마를 소진해야만 정화되고 해방될 수 있습니다. [254]

초기 자이나교 요가는 명상, 육체 포기( kāyotsarga ), 묵상 , 반성(bhāvanā) 등 여러 유형으로 나누어진 것으로 보인다 . [255]

불교 요가

고타마 붓다 의 좌선 명상, 갈 비하라 , 스리랑카

이 부분의 본문은 불교 명상 과 불교의 디아나 입니다.

불교 요가는 각성에 대한 37가지 도움을 개발하는 것을 목표로 하는 다양한 방법을 포함합니다 .

그것의 궁극적인 목표는 bodhi (각성) 또는 nirvana (중단)이며, 전통적으로 고통( dukkha )과 중생 의 영구적인 끝으로 간주됩니다 . [주 21]

불교 경전 은 요가 외에

bhāvanā ("발달") [주 22] 및 jhāna/dhyāna 와 같은 영적 실천 에 대한 여러 용어를 사용합니다 . [주 23]

초기 불교 에서 요가 수행에는 다음이 포함되었습니다 .

네 가지 디야 나(네 가지 명상 또는 정신 집중),

사띠 팟타나 (마음챙김 의 기초 또는 확립),

아나빠나사띠 (호흡에 대한 마음챙김),

네 가지 무형의 거처 (초자연적인 마음 상태),

brahmavihārās ( 신성한 거처).

Anussati (사색, 회상)

이러한 명상은 윤리 , 올바른 노력 , 감각 억제 및 올바른 견해 와 같은 고귀한 팔정도 의 다른 요소에 의해 뒷받침되는 것으로 여겨졌습니다 . [256]

불교에서 요가 수행에 없어서는 안 될 두 가지 정신 특성 인

사마타 (고요함, 안정)와 위빠사나 (통찰력, 명료한 보기)가 있다고 합니다.

Samatha 는 안정적이고 편안한 마음으로

samadhi (정신적 통일, 집중) 및 dhyana (명상에 몰두하는 상태 ) 와 관련이 있습니다.

위파사나 "사물을 있는 그대로 보는 것"( yathābhūtaṃ darśanam ) 으로 정의되는

현상의 진정한 본질에 대한 통찰 또는 꿰뚫는 이해 입니다.

고전 불교의 독특한 특징은 모든 현상( 담마 )을 자아가 없는 것으로 이해하는 것입니다. [258] [259]

이후 불교 전통의 발전은 요가 수련의 혁신으로 이어졌습니다.

보수적인 상좌부 학파는

후기 작품에서 명상과 요가에 대한 새로운 아이디어를 발전시켰는데,

그 중 가장 영향력 있는 것은 청정도론 입니다.

Mahayana 명상 가르침은

Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra 에서 볼 수 있습니다 .

4세기. 대승은

또한 만트라 와 다라니 의 사용 ,

정토 또는 불경 에 환생을 목표로 하는 정토 수련 ,

시각화 와 같은 요가 방법을 개발하고 채택했습니다 .

중국 불교 는 Koan 성찰과 Hua Tou 의 선 수행을 발전시켰습니다 .

탄트라 불교 는

신 요가 , 구루 요가 , Naropa , Kalacakra , Mahamudra 및 Dzogchen 의

여섯 가지 요가 를 포함하여

티베트 불교 요가 시스템의 기초가 되는 탄트라 방법을 개발하고 채택했습니다 . [260]

클래식 요가

이 부분의 본문 은 요가(철학)입니다 .

종종 고전 요가, 아쉬탕가 요가 또는 라자 요가 라고 불리는 것은

주로 파탄잘리의 이원론적 요가 수트라에 설명된 요가입니다 .

고전 요가 의 기원은 불분명하지만

이 용어에 대한 초기 논의는 우파니샤드에 나타난다.

Rāja 요가 (왕의 요가)는 원래 요가의 궁극적인 목표를 나타냈습니다.

samadhi , [ 262]

그러나 Vivekananda 에 의해 아쉬 탕가 요가의 일반적인 이름으로 대중화 되었습니다 . [263] [261]

요가 철학은 기원후 1천년 후반에 힌두교 의 뚜렷한 정통 학파( darsanas ) 로 간주되었습니다 . [20] [웹 1]

고전 요가는 인식론, 형이상학, 윤리적 실천, 체계적인 운동, 몸과 마음과 영혼을 위한 자기 계발을 통합합니다.

그 인식론 ( pramana )과 형이상학은 Sāṅkhya 학파 와 유사합니다 .

고전 요가의 형이상학은 상캬의 것과 마찬가지로 주로 두 개의 뚜렷한 현실을 상정합니다:

프라크리티 (자연, 세 개의 구나 로 구성된 물질 세계의 영원하고 활동적인 무의식적 근원 )와

뿌루샤 (의식), 세계의 지적 원리인 복수의 의식 . 목샤 ( 해방 ) 는

puruṣa 는 쁘라끼르띠(prakirti)에서 나온 것으로,

생각의 파동( citta vritti )을 고요히 하고 뿌루샤에 대한 순수한 자각 속에서 쉬는 명상을 통해 달성됩니다 .

무신론적 접근을 취하는 상키야와는 달리, [147] [265]

힌두교 의 요가 학교는

"개인적이지만 본질적으로 활동하지 않는 신"

또는 "개인 신"( Ishvara )을 받아들입니다. [266] [267]

아드바이타 베단타

Raja Ravi Varma 의 제자들과 함께 있는 Adi Shankara (1904)

Vedanta 는 다양한 하위 학교와 철학적 견해를 가진 다양한 전통입니다.

그것은 우파니샤드 와 브라흐마 수트라 (초기 텍스트 중 하나) 연구에 초점을 맞추고 있으며 ,

브라만 에 대한 영적 지식( 불변하고 절대적인 실재)을 얻는 것에 대해 다루고 있습니다. [268]

Vedanta의 초기이자 가장 영향력 있는 하위 전통 중 하나는 비이원론적 일원론 을 가정하는 Advaita Vedanta 입니다.

브라만(절대 의식)과 아트만(개별 의식)의 동일성을 실현하는 것을 목표로 하는 갸나 요가 (지식의 요가)를 강조 합니다. [269] [270]

이 학파의 가장 영향력 있는 사상가는 갸나 요가에 대한 주석과 기타 작품을 저술한 Adi Shankara (8세기)입니다.

Advaita Vedanta에서 jñāna는 경전, 구루 , 그리고 가르침을 듣는(그리고 명상하는) 과정을 통해 달성됩니다. [271]

차별, 포기, 평온, 절제, 냉정, 인내, 믿음, 관심, 지식과 자유에 대한 열망과 같은 자질도 바람직합니다.

Advaita 의 요가는 "특정한 것에서 물러나고 보편자와 동일시하는 명상적 운동으로, 자신을 가장 보편적인 것, 즉 의식으로 생각하게 합니다." [273]

Yoga Vasistha 는 아이디어를 설명하기 위해 짧은 이야기와 일화 를 사용하는 영향력 있는 Advaita 텍스트 [274] 입니다.

요가 수련의 7단계를 가르치는 이 책은 중세 아드바이타 베단타 요가 학자들의 주요 참고 문헌이자

12세기 이전의 힌두 요가에 관한 가장 인기 있는 문헌 중 하나였습니다.

Advaita 관점에서 요가를 가르치는 또 다른 텍스트는 Yoga Yajnavalkya 입니다 . [276]

탄트라 요가

상위 문서: 탄트라

Samuel에 따르면 Tantra는 경쟁 개념입니다. [194]

탄트라 요가는 기하학적 배열과 그림( 만다라 ), 남성 및 (특히) 여성 신, 삶 을 사용하여 정교한 신 시각화와 함께

요가 수행을 포함하는 9~10세기

불교 및 힌두교(Saiva, Shakti) 텍스트의 관행으로 설명될 수 있습니다. -

무대 관련 의식, 차크라 와 만트라 의 사용 ,

건강, 장수, 해방을 돕는 성적 기술. [194] [277]

하타요가

Viparītakaraṇī , 아사나와 무드라 로 사용되는 자세 [278]

상위 문서: 하타 요가

하타 요가는 다음 세 가지 힌두 경전에서 주로 설명하는

신체적, 정신적 근력 강화 운동과 자세에 중점을 둡니다. [279] [280] [281]

스바트마라마( Svātmārāma)의 하타 요가 프라디 피카(15세기)

Shiva Samhita , 작가 미상(1500 [282] 또는 17세기 후반)

게란다의 게란다 삼히타 (17세기 후반)

일부 학자들은 고락샤나트 의 11세기 고락샤 삼히타 를 목록에 포함하는데,

이는 고락 샤나트가 오늘날의 하타 요가 대중화에 책임이 있는 것으로 간주되기 때문입니다. [283] [284] [285]

인도의 마하시다스가 창시한 금강승 불교는 [ 286 ]

하타 요가와 유사한 일련의 아사나와 프라나야마(예: tummo ) [200] 를 가지고 있습니다 .

라야와 쿤달리니 요가

하타 요가와 밀접한 관련이 있는

라야 요가와 쿤달리니 요가 는

종종 독립적인 접근 방식으로 제시됩니다. [37]

Georg Feuerstein 에 따르면 ,

라야 요가(해체 또는 병합의 요가)는 "명상적 흡수( laya )에 초점을 맞춥니다.

라야 요가는 소우주, 마음을 초월적 자의식."

Laya 요가에는 "내면의 소리"( nada ), Khechari 및 Shambhavi mudra와 같은 mudras, 깨어나는 kundalini ( 신체 에너지) 듣기를 포함하는 여러 기술이 있습니다. [288]

쿤달리니 요가는

호흡과 몸의 기술로

몸과 우주의 에너지 를 일깨워 우주 의식과 결합시키는 것을 목표로 합니다.

일반적인 교육 방법은 가장 낮은 차크라 에 있는 쿤달리니 를 깨우고

중앙 채널을 통해 머리 꼭대기에 있는

가장 높은 차크라에 있는 절대 의식과 결합하도록 안내합니다. [290]

다른 종교의 수용

기독교

일부 기독교인 은

힌두교 의 영적 뿌리 에서 벗어난 요가의 신체적 측면 과

동양 영성의 다른 측면을

기도 , 명상 및 예수 중심의 확언과 통합합니다. [291] [292]

이 관행에는 (원래의 산스크리트어 용어 를 사용하는 대신) 영어로 포즈의 이름을 바꾸는 것과

관련된 힌두 진언 과 요가 철학을 포기하는 것도 포함됩니다 .

요가는 기독교 와 연관되고 재구성됩니다 .

이것은 문화적 전유 혐의를 불러 일으켰습니다.

다양한 힌두교 그룹에서; 학자 들은 여전히 회의적입니다 .

이전에 로마 카톨릭 교회 와 일부 다른 기독교 단체 는

요가와 명상을 포함 하는

일부 동양 및 뉴에이지 관행 에 대해 우려와 반대를 표명 했습니다. [295] [296] [297]

1989년과 2003년에 바티칸 은

기독교 명상의 측면 과 " 뉴에이지에 대한 기독교적 성찰 "이라는 두 가지 문서를 발행했는데 ,

이는 대부분 동양과 뉴에이지 관행에 비판적이었습니다.

2003년 문서는 바티칸의 입장을 자세히 설명하는 90페이지 분량의 핸드북으로 출판되었습니다. [298]

바티칸은 명상의 물리적 측면에 대한 집중이

"신체 숭배로 변질될 수 있다"고 경고했으며,

신체 상태를 신비주의와 동일시하는 것은

"심령적 혼란과 때로는 도덕적 일탈로 이어질 수도 있다"고 경고했다.

이것은 교회가 영지주의자들을 반대했던 초기 기독교 시대에 비유되어 왔습니다.

구원은 믿음으로 오는 것이 아니라

신비로운 내적 지식으로 온다는 믿음. [ 291]

편지는 또한 "다른 종교와 문화에서 개발된 명상 방법으로 [기도]가 풍부해질 수 있는지

그리고 어떻게 풍부해질 수 있는지 알 수 있습니다"라고 말하지만 "

[ 궁극적 실재에 대한 기도와 기독교 신앙에 대한 다른 접근" [291] 어

떤 [ 어떤? ] 근본주의 기독교 단체들은 요가를 기독교와 일치하지 않는 뉴에이지 운동 의 일부로 간주하여

그들의 종교적 배경과 양립할 수 없는 것으로 간주합니다 . [300]

이슬람교

11세기 초 페르시아 학자 Al-Biruni 는 인도를 방문하여

16년 동안 힌두교도와 함께 살았고

(그들의 도움으로) 여러 산스크리트어 작품을 아랍어와 페르시아어로 번역했습니다.

이들 중 하나는 Patanjali의 Yoga Sutras 였습니다. [301] [[[Wikipedia:Citing_sources|page needed]]]_327-0' class=reference >[302]

Al-Biruni의 번역은 Patañjali의 요가 철학의 많은 핵심 주제를 보존했지만

일부 경전과 주석은 일신교 이슬람 신학과의 일관성을 위해 다시 작성되었습니다. [301] [303]

Al-Biruni의 요가 경전 버전은 약 1050년 까지 페르시아와 아라비아 반도 에 도달했습니다 .

16세기 동안 하타 요가 텍스트 Amritakunda 는 아랍어와 페르시아어로 번역되었습니다. [304]

그러나 요가는 주류 수니파 와 시아파 이슬람교 에서 받아들여지지 않았습니다 .

특히 남아시아 의 신비한 수피 운동 과 같은 소수 이슬람 종파는

인도 요가 자세와 호흡 조절을 채택했습니다. [305] [306]

16세기 Shattari Sufi이자 요가 텍스트 번역가인 Muhammad Ghawth는

요가에 대한 관심 때문에 비판을 받았고

수피 신앙 때문에 박해를 받았습니다. [307]

말레이시아의 최고 이슬람 단체는

법적 으로 시행 가능한 2008년 파트와(fatwa)를 부과하여

무슬림 이 요가 를 하는 것을 금지 했습니다 . [308] [309]

수년 동안 요가를 수련해 온 말레이시아 무슬림들은

그 결정을 "모욕적"이라고 불렀습니다. [310]

말레이시아 여성인권단체 이슬람의 자매회(Sisters in Islam )는

요가가 운동의 한 형태라고 말하며 실망감을 표시했다. [311]

말레이시아 총리는 운동으로서의 요가는 허용되지만

종교적 진언을 외우는 것은 허용되지 않는다고 밝혔습니다. [312]

인도네시아 울레마 위원회 (MUI)는 2009년

요가에 힌두교 요소가 포함되어 있다는 이유로

요가를 금지하는 파트와를 부과했습니다 .

이 fatwas 는 인도 의 Deobandi 이슬람 신학교 인 Darul Uloom Deoband 에 의해 비판을 받았습니다 . [314]

2004 년 이집트 의 그랜드 무프티 알리 고마( Grand Mufti Ali Gomaa )와 그 이전에 싱가포르의 이슬람 성직자들에 의해 힌두교와의 연관성 때문에

요가를 금지하는 유사한 파트와스(fatwa)가 부과되었습니다. [315] [316]

이란의 요가 협회에 따르면

2014년 5월 현재 이란에는 약 200개의 요가 센터가 있습니다 .

보수주의자들은 반대했다. [317]

2009년 5월 터키 종교국장 인 알리 바르다콜루( Ali Bardakoğlu )는

영기 및 요가 와 같은 개인 개발 기술 을 극단주의로 이어질 수 있는 상업적 벤처로 할인했습니다.

Bardakoğlu에 따르면 레이키와 요가는

이슬람을 희생시키면서 개종하는 한 형태가 될 수 있습니다. [318]

Nouf Marwaai 는 사우디 아라비아 에 요가를 가져왔습니다

.2017년 요가를 "비이슬람"이라고 주장하는 그녀의 커뮤니티로부터 위협을 받고 있음에도 불구하고

요가를 합법화하고 인정하는 데 기여했습니다. [319]

또한보십시오

아사나 목록

현대 요가 전문가

요가 학교 목록

태양 인사말

요가 관광

요기

노트

^^이동:a b c Bryant(2009, p. xxxiv): "대부분의 학자들은 통용 기원(약 1세기에서 2세기)이 된 직후에 본문의 연대를 추정합니다."

^ 원문 산스크리트어: 유세 남자 풋 유세 티오 비프라 비프라시 부토 비피치타. 그는 와나비데크 인마히 데바시 독립 운동에 참여했습니다. [32]

번역 1 : 광대한 조명을 받은 선견자의 선견자는 요가적으로 [유자테, 윤잔테] 그들의 마음과 지능을 통제합니다... (…) [30]

번역 2 : 조명을 받은 멍에 그들의 마음과 그들은 그들의 생각을 조명하는 신에게 멍에를 매었습니다 , 광대하고 의식이 빛나는 것;

지식의 모든 현시를 아시는 유일한 분이신 그분만이 희생의 일을 지시하십니다. 창조의 신격인 사비트리에 대한 찬양은 위대합니다. [31]

^ Gavin Flood (1996), Hinduism , p.87–90, "The orthogenetic theory" 및 "Non-Vedic origins of renunciation"을 참조하십시오. [58]

^ 고전 이후의 전통은 Hiranyagarbha 를 요가의 창시자로 간주합니다. [60] [61]

^ Niniam Smart in Doctrine and argument in Indian Philosophy , 1964, pp. 27–32, 76 [65] , SK Belvakar 및 Inchegeri Sampradaya in History of Indian Philosophy , 1974 (1927)와 같은 다른 학자들이 Zimmer의 관점을 뒷받침합니다), pp. 81, 303–409. [66]

^^ 왜냐하면 포기와 베다 브라만교 사이에 연속성이 의심할 여지 없이 발견될 수 있는 반면,

브라만교가 아닌 스라마나 전통의 요소도 포기 이상을 형성하는 데 중요한 역할을 했기 때문입니다.

실제로 베다 브라만교와 불교 사이에는 연속성이 있으며,

붓다는 자신의 시대에 침식된 것으로 보았던 베다 사회의 이상으로 돌아가고자 했다고 주장되었습니다."[72]

↑ 현재 일부 학자들은 이 이미지가 유라시아 신석기 신화에서 발견되는 야수왕의 예이거나고대 근동 및 지중해 예술 에서 발견되는 동물의 주인에 대한 널리 퍼진 모티프라고 생각하고 있습니다. [79] [80]

^^ Wynne은 "초기 브라만 문학에서 가장 초기이자 가장 중요한 우주 발생론적 소책자 중 하나인 Nasadiyasukta는 초기 브라만 명상의 전통과 밀접한 관련이 있음을 시사하는 증거를 포함하고 있습니다.

이 텍스트를 자세히 읽어보면 초기 브라만 관조의 전통. 이 시는 관조에 의해 작곡되었을 수 있지만

그렇지 않더라도 인도 사상의 관조/명상 경향의 시작을 표시한다고 주장할 수 있습니다. [82]

Miller는 Nasadiya Sukta와 Purusha Sukta 의 구성 이 "마음과 마음의 흡수라고 하는 가장 미묘한 명상 단계"에서 발생한다고 제안합니다.

이 단계는 선견자가 "신비한 심령과 우주의 힘을 탐구합니다..."를 통해 "고조된 경험을 포함합니다." [83]

Jacobsen은 dhyana(명상)가 "시각적 통찰력", "시각을 자극하는 생각"을 의미하는 Vedic 용어 dhih에서 파생되었다고 기록합니다. [83]

^ 원본 산스크리트어 : स स 효야 मिक न효치 사용 용고 ध ध효사 तिष효사 용고 संप효사 용고 संप संप효야 संप효율 용고 प 효치 사; 음 – Chandogya Upanishad , VIII.15 [91]

Translation 1 by Max Muller , The Upanishads, The Sacred Books of the East – Part 1, Oxford University Press: (그는) 독학으로 자신의 모든 감각을 자아에 집중합니다.

띨르타를 제외하고는 어떤 피조물에게도 고통을 주지 않으며, 평생 그렇게 행동하는 사람은 브라만 의 세계에 도달하고 돌아오지 않습니다. 참으로 그는 돌아오지 않습니다.

GN Jha의 번역 2: Chandogya UpanishadVIII.15, page 488: (자기 연구에 종사하는 사람), - 모든 감각 기관을 진아 속으로 집어넣고,

- 특별히 지정된 장소를 제외하고는 어떤 생명체에게도 고통을 주지 않는 사람,

- 내내 그렇게 행동하는 사람 생명 은 브라만의 영역에 이르고 돌아오지 않는다, 그래, 돌아오지 않는다.

^ 고대 인도 문학은 구전 전통 을 통해 전승되고 보존되었습니다 . [97]

예를 들어, 가장 초기에 작성된 팔리어 정경 텍스트는 붓다의 입멸 후 수 세기가 지난 기원전 1세기 후반으로 거슬러 올라갑니다. [98]

↑ 팔리어 정경의 날짜에 대해 그레고리 쇼펜(Gregory Schopen)은 다음과 같이 썼다.

기원전 1세기의 마지막 분기, Alu-vihara 편집 날짜, 우리가 어느 정도 지식을 가질 수 있는 가장 초기의 편집,

그리고 중요한 역사를 위해 그것은 기껏해야 다음의 출처로만 사용될 수 있습니다.

그러나 우리는 또한 이것조차 문제가 있다는 것을 알고 있습니다... 사실 그것은 Buddhaghosa, Dhammapala 및 기타 주석의 시간, 즉 CE 5-6세기까지입니다.

우리는 [팔리어] 정경의 실제 내용에 대해 확실한 것을 알 수 있습니다." [113]

↑ 이 우파니샤드의 날짜에 대해서는 "Akademie der Wissenschaften und Literatur"의 1950년 절차에서 Helmuth von Glasenapp도 참조하십시오 [114].

↑ 현재 존재하는 Vaiśeṣika Sūtra 필사본은 기원전 2세기와 기원 서기 시작 사이에 완성되었을 가능성이 높습니다.

Wezler는 무엇보다도 요가 관련 텍스트가 나중에 이 Sutra에 삽입되었을 수 있다고 제안했습니다.

그러나 Bronkhorst는 Wezler와 동의하지 않는 부분이 많습니다. [135]

^ Werner는 "요가라는 단어는 완전히 전문적인 의미, 즉 체계적인 훈련으로 여기에 처음으로 등장하며 이미 다른 중간 우파니샤드에서 다소 명확한 공식을 받았습니다....

체계화의 추가 과정 궁극적인 신비주의적 목표에 이르는 길로서의 요가는 후속 요가 우파니샤드에서 분명하며

이러한 노력의 절정은 파탄잘리가 이 길을 여덟 가지 요가 체계로 성문화한 것으로 표현됩니다." [152]

^ 요가라고 불리는 철학 체계의 창시자인 Patanjali 에 대해서는 Chatterjee & Datta 1984 , p. 42.

↑ 6개 정통파에 대한 개요와 학교 그룹화에 대한 자세한 내용은 Radhakrishnan & Moore 1967 , "Contents" 및 pp. 453–487을 참조하십시오.

^ 요가 철학 학교에 대한 간략한 개요는 다음을 참조하십시오. Chatterjee & Datta 1984 , p. 43.

^ Worthington은 "요가는 자이나교에 대한 부채를 완전히 인정하고 자이나교는 요가 수행을 삶의 일부로 만들어 보답합니다."라고 썼습니다. [186]

↑ "Tantra"라는 단어의 가장 초기 문서화된 사용은 Rigveda (X.71.9)에 있습니다. [193]

^ "산스크리트어 'dhyāna'에서 중국어로 'Ch'an'이라고 불리는 명상 학교는 서양에서 일본어 발음 'Zen ' 으로 가장 잘 알려져 있습니다." [207]

↑ 예를 들어, Kamalashila(2003), p. 4, 불교 명상은 " 깨달음 을 궁극적인 목표로 삼는 모든 명상 방법을 포함한다." 마찬가지로 Bodhi(1999)는 다음과 같이 썼습니다.

Nibbana ..." Fischer-Schreiber et al. 에 의해 약간 더 넓은 정의가 제공되지만 유사한 정의가 제공됩니다(1991), p. 142: "

명상– 종종 방법은 상당히 다르지만 수행자의 의식을 '각성', '해방', '깨달음.'" Kamalashila(2003)는 또한 일부 불교 명상이 "보다 준비적인 성격"이라는 것을 허용합니다(p. 4).

^ Pāli 와 Sanskrit 단어 bhāvanā 는문자 그대로 "정신 발달"에서와 같이 "발달"을 의미합니다.

이 용어와 "명상"의 연관성에 대해서는 Epstein(1995), p. 105; 및 Fischer-Schreiber et al. (1991), p. 20.

팔리어 정경 의 잘 알려진 담론의 예로서"라훌라에 대한 더 큰 권면"( Maha-Rahulovada Sutta , MN 62), Ven. Sariputta 는 Ven에게 말합니다.

Rahula ( VRI, nd 에 기반한 팔리어: ānāpānassatiṃ, rāhula, bhāvanaṃ bhāvehi. Thanissaro(2006) 는 이것을 다음과 같이 번역합니다.